That’s a good and still unanswered question. Most people think that cappuccino is an Italian drink, but few know that, yes, it may have been invented by an Italian, but definitely not in Italy, where it wasn’t even mentioned until the 1930s.

That’s a good and still unanswered question. Most people think that cappuccino is an Italian drink, but few know that, yes, it may have been invented by an Italian, but definitely not in Italy, where it wasn’t even mentioned until the 1930s.

King Jan Sobienski of Poland

Its birthplace was Vienna, but probably with a Polish inventor. The Polish Connection: Two versions of its origin date to the Battle of Vienna in 1683. On September 12 the army of the Holy Roman Empire led by the Polish King Jan (John) III Sobienski attacked the vastly larger army of the Ottoman Empire, which for three months had been laying siege to Vienna. After a 15-hour battle Sobienski’s troops, which included the famous mounted Hussars, routed the Turks and captured the tent of Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha. He escaped and the Battle of Vienna put an end to the Ottoman attempt to conquer Europe. To commemorate the victory for Christendom, Pope Innocent XI proclaimed the date “Festa del Santissimo Nome di Maria” or “The Most Holy Name of Mary Devotion”. The fleeing Ottoman troops left behind many items, including bags of a hard black bean that was largely unknown in Europe. From it, the Turks had customarily made a drink they called khafir. Before long, the Viennese followed suit.

Pope Innocent XI

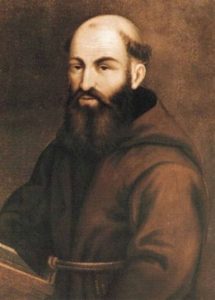

The Italian Connection: Another version recounts that Blessed Marco d’Aviano, an Italian Capuchin friar and papal legate in Vienna, who’d rallied the Christian troops with prayer before the Battle, had found the Turks’ abandoned sacks of coffee and brewed some. Finding it too bitter, he added some honey and milk and soon the Viennese were calling it “kapunziner” or “little Capuchin” or cappuccino in his honor and for the color of his habit. St. John Paul II beatified D’Aviano on April 27, 2003 not for his uncertain coffee connection, but for offering his life to God for the salvation of the Christian faith and civilization in Vienna, Buda (1686) and Belgrade (1688) thus re-establishing peace in Europe, as well as for his intervention to spare the lives of 800 captured Ottoman soldiers/prisoners of war after their defeat in Belgrade.

Blessed Marco d’Aviano

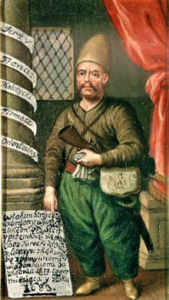

Polish again: The website www.thecompassnews.org reports another story: “…that Jan Sobieski had a spy, a Polish merchant or Polish army officer, who’d travelled or lived in the Middle East and was fluent in Turkish. The spy, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, was able to get behind enemy lines dressed in Turkish attire and bring intelligence back to the king, as well as get safely out of the besieged city to alert reinforcements. So, after the Battle, Kulczycki was rewarded with the abandoned Turkish coffee beans and he used them to open Vienna’s first coffee house at Schlossergassl near St. Stephen’s Cathedral. It was named “Hof zur Blauen Flasche” (House Under the Blue Bottle). At first the bitter drink wasn’t popular, but Kulczycki mixed in milk and honey and business blossomed. Added to that was the fact that Kulczycki would dress in Turkish attire to serve customers, attracting more people.” Until recently, every year in October café owners in Vienna decorated their windows with Kulczycki’s portrait. Since 1885 he’s memorialized by his statue wearing his Turkish outfit on Vienna’s namesake street Kolschitzkystrasse at the corner of his house at Favoritenstrasse 64. There is also a portrait of him in Krakow’s Czartoyski Museum, now closed for restoration through December and also home to Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine.

Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki

Although their cappuccino connection make for a romantic tale, neither D’Aviano or Kulczycki was its inventor. Yes, coffee didn’t reach Europe until the 17th century (from Ethiopia via Arabia and the Middle East), but by the time the Turks were besieging Vienna there were already coffee houses in Italy, England, and France. Thus cappuccino’s who, when, and where remain a mystery, but coffee’s popularity had already alarmed The Church and many priests, who called it “Satan’s drink” because it was the drink of infidels, wanted it banned. Pope Clement VIII (1536-1605) refused to until he’d sampled a drop himself in 1600. According to legend, he commented: “The devil’s drink is delicious, so we should cheat the devil by baptizing it.” The rest is history.

Pope Clement VIII

Speaking of history, the best cappuccino in Warsaw is at the Café Bristol in the historical Hotel Bristol. In Italy, the subject of a forthcoming article, since Trieste was the only port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is still an important port for coffee importation, it logically has the longest tradition of historical literary cafés like Vienna: Caffè San Marco, Caffè degli Specchi, Antico Caffè Torino, Caffè Stella Polaris, and Caffè Tommasseo; although not close by geographically the tradition is a close second in Turin: Al Bicerin, Café Florio’s, Baratti & Milano, Caffè Mulassano, Caffè San Carlo, Caffè Torino, Platti, and Abrate. In Bergamo head to Caffè Tasso and in Cosenza Gran Caffè Renzelli; in Milan Gin Rosa, Bar Magenta, Cafè Bistrot Savini, Camparino and Bar Jamaica; in Venice Quadri or Florian; in Padua Pedrocchi; in Florence Caffè Gilli, Caffe Paszkowski, Gran Caffè Giubbe Rosse and Caffè Rivoire; in Rome the Caffé Greco, and in Naples Gambrinus. Italians generally agree that Naples offers the best espresso and cappuccino because of the water there. Outside Italy: Caffé Sant’Ambroeus on Madison Avenue in New York City.

At Gambrinus