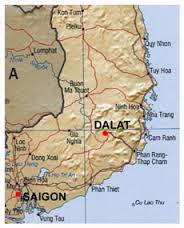

Located in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, the picturesque town of Dalat is a corner of France in the tropics. Created as a hill station from a barren plateau in the early 20th century by the French colonial powers, modern-day Dalat retains much of its European influence, making it an almost surreal Vietnamese version of a small town in the French Alps.

Located in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, the picturesque town of Dalat is a corner of France in the tropics. Created as a hill station from a barren plateau in the early 20th century by the French colonial powers, modern-day Dalat retains much of its European influence, making it an almost surreal Vietnamese version of a small town in the French Alps.

By the end of the 19th century, France had colonies in Asia, North Africa and the Caribbean, but by far, the most difficult place for colonists to live was Indochina, the region now made up of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Early settlers found the heat and humidity of the deltas and lowlands to be stifling, with disease followed by a quick death a common fate. Reports indicate that some French soldiers lasted just days before finding life literally unbearable. The only options for unwell colonists was to be shipped off to cooler climes in Yokohama, Japan or on a slow boat to France, some 6,000 miles away. Many did not survive the journey.

So began a project to find a local hill station in Indochina, a place to restore health and wellness with cooler temperatures and living conditions similar to home, much like the British had Darjeeling in India and the Dutch had Bogor in Indonesia.

At times Dalat is reminiscent of a French Mediterranean resort.

Once the desolate Lang Bian plateau was selected, work began in earnest to build a spa town mimicking a slice of Europe in Asia. While the high altitude (4,900 feet) allowed for Mediterranean-like cool temperatures, it initially meant that every kind of supply had to be carried up steep hills on “human backs.” This would have to change sooner rather than later, as the colonial powers envisioned comfortable villas, thriving communities, experimental farms and even an administrative hub and a military base in Dalat.

A railway linking Dalat to Hanoi in the north and Saigon in the south soon got underway. However, the steep terrain (with gradients of up to 120mm/m) proved challenging. The first 25 miles of the railway from the coast towards Dalat used conventional adhesion rail technology, but it would take another 13 years to cover the final 27 miles using cog technology, much like that used in the Darjeeling Himalayan Hill line in British India.

When the line was finally completed, visitors arrived at a train station modeled after the Deauville-Trouville station in Normandy. “It is as if one passed without warning from one country to another, each having different geography, climate, and customs,” wrote one Dalat visitor of her train journey.

Dalat was built to give the French colonists a taste of France in the tropics. In addition to rowing parties, tennis tournaments, horse races and hunting, part of Dalat’s appeal was that its temperate climate allowed for growing European fruits and vegetables, a welcome change from imported canned goods and strange local foodrs. The French were soon busy growing artichokes, red lettuce, Brussels sprouts, radishes and  strawberries, not to mention European varieties of flowers, along with coffee and tea.

strawberries, not to mention European varieties of flowers, along with coffee and tea.

Nowadays, Dalat is still the produce capital of Vietnam. Every valley in and around the town is filled with greenhouses growing many of the same types of fruits, vegetables and flowers that the French introduced. The Dalat market looks much like a European farmer’s market with attractive displays of cauliflower, broccoli, artichoke and giant strawberries. While Dalat cuisine makes use of these unique ingredients (in dishes like the canh atiso, a healthy clear broth soup made from a whole artichoke flower and flavored with spare ribs or pork feet), there are very few dishes that can claim to have originated from Dalat, mainly because its original residents came from all parts of Vietnam. Instead, some of its cuisine is a Vietnamese take on classic French dishes.

Dalat Train Café

Chad Kubanoff, a chef trained in classical French cuisine and now Vietnamese street food expert, mentions Vietnamese bo kho (beef stew) as an example. “It’s a dish that most travelers don’t expect to see or taste in Vietnam. It is very ‘un-Vietnamese’ in its richer flavor and full-bodied broth. Also serving a broth-based dish with a baguette is very rare to see in this country, definitely an ode to its French roots. Another nod to the French is having a piece of pâté or cheese stuffed in bread, as is the concept of eating eggs and bread for breakfast.” Visitors to Vietnam will also delight in its strong coffee (another product introduced by the French). The Vietnamese version, however, requires some patience, as it slowly drips through a single-serve filter before getting a dollop of condensed milk, the result being a velvety, almost chocolate-tasting concoction.

Blues musician Curtis King, refurbished an old train car into a pleasant cafe. He and his wife also run the V Cafe downtown where you can hear him play.

In its heyday in the 1940s, Dalat had 750 private villas and was home to 20,000 permanent residents and the same number of annual visitors. Some of those villas remain, most notably in the “French Quarter” of the town ― some abandoned shells of their former glory, while others have been fully and beautifully restored.

One of the town’s most charming intersections of travel and food is the Dalat Train Villa and Café. Situated in a cluster of colonial-era stone villas rumored to have housed French families who worked on the railway, the cafe is actually a restored 1910 train carriage, serving up a Vietnamese and international menu at very reasonable prices. Some of the French-inspired menu items include Spicy Vietnamese Bo Kho (USD 4), a Dalat Green Salad (USD 2.50) as well as a mean cup of local Dalat coffee (USD 1.50).

Dalat Train Villa

While the main Dalat train line closed to the public in 1969, train lovers might want to take a 10 minute stroll downhill from the café to the restored Dalat train station and take a trip to the only stop — Trai Mat, a little town 5 miles away whose main attraction is the mosaicked Linh Phuoc Pagoda (USD 2 one way, leaving on a regular schedule when there are at least 20 passengers for the 1.5 hour round trip, including almost an hour to visit the sights).