The refrain of the Morcheeba, a British trip hop Band, tells us repeatedly in the most famous hit of their 2000 album, “Fragments of Freedom,” “Don’t you know that Rome wasn’t built in a day.” Indeed so, Rome, a layer-cake of history built on seven hills, is appropriately nicknamed “The Eternal City” because visitors can see monuments and art from almost every period of her c.2,300-year history: ancient Greek, Republican Rome, Imperial Rome, Medieval (if not so much), Renaissance, Baroque, Art Deco, Fascist, and contemporary.

In all fairness the Janiculum, outside the boundaries of the ancient city and across the Tiber from the other proverbial seven, should be considered Rome’s eighth hill. In ancient times it was the center for the cult of the two-faced (one looking towards the past, the other the future) god Janus; the fact that it overlooked the city made it a good place for augurs to observe the auspices. Wikipedia’s entry tells us: “According to Livy, the Janiculum was incorporated into ancient Rome during the time of the king Ancus Marcius in order that it not be occupied by an enemy. It was fortified by a wall and a bridge constructed across the Tiber to join it to the rest of the city.” Still today one of the best locations for a scenic view of downtown Rome’s innumerable domes and bell towers, it’s crowned on its crest by the American Academy in Rome designed by the turn-off-the 20th-century New York-based architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White. It’s encircled for ¾ of its base by the artsy neighborhood of Trastevere (meaning across the Tiber) and for the other ¼ by Vatican City.

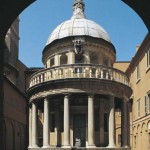

Near its summit, two blocks from the American Academy, is the magnificent church San Pietro in Montorio, built on the site of an earlier 9th-century church and commissioned by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, who owned the land. It’s a favorite choice for weddings because of its view over the city. According to one legend, it was the site of St. Peter’s crucifixion. In its cloister is the Tempietto, a small commemorative martyrium (tomb or shrine) also commissioned by Ferdinand and Isabella. Designed by the Florentine architect Bramante and later Michelangelo’s model for St. Peter’s dome, this, Bramante’s first Roman work, is considered a masterpiece of High Renaissance Italian architecture. Between the church and the American Academy is a splendid Baroque fountain, the Fontana dell’Acqua Paola, built by Pope Paul V in 1612 to celebrate the reopening of an old Roman aqueduct.

In 1849 the Janiculum was the site of a battle between the forces of Garibaldi, defending the revolutionary Roman Republic against French forces, who were fighting to restore Pope Pius IX’s temporal power over Rome. Because of this battle there are several monuments on the Janiculum to Garibaldi and to his compatriots in the wars of Italian independence (1848-70) who gave their lives to create modern united Italy. The most imposing of these are the white marble Independence War Memorial near the Acqua Paola and past the American Academy the equestrian statues of Garibaldi, supposedly scowling over his shoulder at the Vatican, and of his wife Anita, who fought alongside him, with a pistol in her right hand and her newborn child in the left. Just beyond Anita is an oddly situated lighthouse built in 1911. It was a gift to Rome from Italian immigrants in Argentina.

Wikipedia’s entry also tells us: “Daily at noon, a cannon fires once from the Janiculum in the direction of the Tiber to signal the exact time. This tradition goes back to December 1847, when the cannon of Castel Sant’Angelo gave the sign to the surrounding belltowers to start ringng at midday. In 1904, the ritual was transferred to the Janiculum and continued until 1939. On April 21 [traditionally Rome’s birthday] 1959, popular appeal convinced the Comune (City Hall) of Rome to resume the tradition…The hill is featured in the third section of Ottorino Respighi’s famous orchestral piece The Pines of Rome.”

During the 1970s I was the associate editor of The American Academy in Rome’s ancient studies and archeology publications. Twice a day on the no. 41, now no. 870, bus I passed a huge abandoned cream-colored building with gaping windows just across the street from the Pontifical North American College, where Americans study for the priesthood, and Rome’s Children’s Hospital, Bambin Gesù on the Vatican-side slope of the Janiculum Hill.

For centuries this eyesore has belonged to the Torlonia family, originally such successful textile merchants and tailors in fashionable Piazza di Spagna that they opened a small bank and became members of the black or papal aristocracy. Until well after the Second World War the eyesore remained an orphanage for girls only run by nuns.

At the beginning of this millennium the Torlonia family long-termed leased this property to the Spanish hotel chain Meliá, which counts 350 hotels worldwide. It took 11 years to refurbish this location into a luxury urban resort, which opened in the spring of 2012 with 116 rooms of 12 different types. Upon arrival at the gate its typically Roman burnt-orange façade has a Palm Beach/Palm Springs/Caribbean golf club look. Yet it’s only a five-minute walk downhill to St. Peter’s and fifteen to Trastevere or another fifteen across the river to Campo dei Fiori and Piazza Navona.

The renovations uncovered the ruins of the prestigious first-century AD Villa Agrippina, which was the home of the Emperor Nero’s mother. Its gardens extended to where St. Peter’s Basilica is today so that the Saint was probably crucified at the far end Agrippina’s gardens. Many of the Villa’s ancient newly discovered artifacts are displayed in the hotel’s spacious public rooms, which include a brightly sunlit library. All these rooms are decorated in subdued beige and cream with touches of red and black except for the bar with its whimsical red, pink, and purple plush chairs.

The hotel’s vast grounds, which include a magnificent swimming pool and state-of-the–art Wellness Center, are based on Domitia’s Gardens, the Eternal City’s first Botanical Gardens, which belonged to Domitia, the sister of Nero’s father and wife of Emperor Domitian.

The perfect location for a conference, family reunion, wedding or honeymoon, yet the understated luxurious Gran Meliá prides itself on being child-friendly. Its younger guests are encouraged to enjoy their own smaller pool, play freely, but hopefully not unsupervised, in the garden, and to join in activities called “Kids First” organized for them on request: guided tours downtown, drawing and painting, paint your own T-shirt, games and races in the garden, and a daily snack at 5 PM.

All the bedrooms are different. Many of them and most suites, usually decorated in somber colors and with a photograph of a famous Roman work-of-art behind the master bed, have areas especially designed for children, so the accommodations are appropriate for family-holidays. Others can be adjoining. All spacious with large terraces and wonderful views towards St. Peter’s or over the Tiber, the especially nice rooms are nos. 360, 719, and 603. In the low season the price per night of a deluxe room with breakfast is 398 euros and in the high season 547 euros.

Homemade spaghetti with saffron from Navelli in the Abruzzi, on a base of fava bean, pea, and asparagus tip sauce and sprinkled with grated black truffles

Bar of goose liver with gelatin of sweet raisin wine from the island of Pantelleria off Sicily, raspberry drops, and crispy pepper from Jamaica

The Gran Meliá is also proud of its gourmet restaurant “VivaVoce,” helmed by the world-famous two-Michelin-star chef Alfonso Iaccarino from Amalfi, also the owner “Don Alfonso 1890” restaurants in Sant’Agata dei Due Golfi above the Amalfi Coast, in Marrakesh, Macao, and most recently in Dubai. Alexis Miceli from the Dominican Republic is “VivaVoce”‘s Executive chef. Among his specialties are: fried oysters, cous cous with baby octopus in a provola cheese foam and cinnamon, and potato gnocchi filled with creamy mozzarella, baby tomatoes, and oregano. In addition to à la carte, Miceli proposes three seasonal “tasting menus”: Tasting (six courses, 95 euros), Vegetarian (five courses, 85 euros), and Inspiration (four courses selected by the chef, 80 euros).

Other dining options include “Liquid Garden” a pool-side lounge bar in a grove of sweet swelling orange trees, and the rooftop “Lunae Terrace.”

In Italy Meliá operates hotels on Capri, in Como, Genoa and Milan, and a second, less expensive one in Rome at Via Aldobrandeschi 223 off the Via Aurelia, about 3 miles from Vatican City.

Another comfortable hotel, though less glamorous and costly, on the Janiculum, around the corner from the American Academy at the Via delle Mura Gianicolense 107 is the 4-star Grand Hotel Del Gianicolo. Until fairly recently a convent, it has a lovely garden, great views of st. Peter’s, a swimming pool, a gourmet restaurant called “Corte degli Archi,” and is less than a five-minute walk to one of Rome’s chicest, though I think over-rated restaurants, “Antico Arco.” Around the corner and five more minutes beyond is a neighborhood landmark, “Lo Scarpone” at Via San Pancrazio 5. Built on the site of one of Garibaldi’s camps, it has a large patio for outdoor dining in summer and is well known for its fantastic antipasto selection and grilled meats and fish.

Also appreciated for their generous antipasti selections, excellent choice-filled menus, and friendly service, are two family-run neighborhood, untouristy restaurants, “Il Focolare” at Via Gabriele Rossetti 40, and “Il Cortile” at Via Alberto Mario 26. They’re both a fifteen-minute walk in the opposite direction from the Grand Hotel Del Gianicolo (turn left instead of right at the entrance), down Via Carini and near Piazza Rosolino Pilo, where there’s a taxi stand for my readers with tired feet.