In which our Far-Flung Correspondent heads for Venice for the world’s greatest muscle-powered nautical event: the Vogalonga.

Kayakers prepare to enter the Grand Canal in Venice.

Four decades ago in a galaxy far, far away—that is to say, Venice, which is, yes, in Italy, but no, not of this world—Toni Rosa Salva was fed up with the engine-powered craft plying Venice’s lagoon. They made the air hideous with noise and stench; their wakes undermined the foundations of the palazzi lining the canals, damaged the fragile ecosystem of the lagoon, and were killing the unique tradition of Venetian rowing (see below). Therefore he proposed to kith and kin a protest: a vogalonga or long row, a great gathering of man-powered boats to honor the rowing culture and shake a figurative fist at the infestation of motorboats.

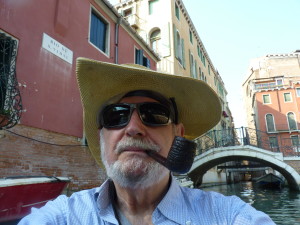

Bill Marsano on the Rio del S Vidal, which connects with the Grand Canal.

Such is the creation myth retailed on www.vogalonga.net. Some few demur, including my Venetian friend Busetto ‘Scarpa’ Vianello, who is among the few veterans of all 40 vogalongas. He says it was only a lark, a nautical parade just for the hell of it. No matter: when events become institutions, legends grow on them like barnacles. Be that as it may, one of Rosa Salva’s pals was boss of Il Gazzettino, Venice’s earnest, occasionally fervid daily newspaper, which published a notice. It said, in effect, ‘come one, come all.’

They did. May 8, 1975 found about 1,500 people in 500 boats thronging the basin of St. Marks, and to the surprise of those who called Venetian rowing a moribund art, almost all the boats were Venetian types Venetianly rowed. Not content with gondolas, Venetians have over the centuries developed several dozen models — as many as 80, Scarpa says — including the Veneta a Quattro, batela, caorlina, sandolo, mascaréta, pupparìn, s’ciopon, gondolino, gondolone, balotina, batela a coa de gambaro, mussìn and vipera. Perhaps 20 survive to this day; others made a vogalonga to oblivion long since. A cannon blast set them off on a course, 32 kilometers or just shy of 20 miles long, that amounted to a grand tour of the Northern Lagoon. It led and still leads east around the tail of Venice, north past such islands as Sant’Erasmo, Venice’s produce garden; Burano, famous for its lace and fiercely painted houses; and then Torcello, with its 11th Century cathedral and Byzantine mosaics. From there south on a long reach to Murano, domain of glass-makers; and another long stretch to the Canale di Canareggio, which repays sweat with glory: a left turn at the end begins the gaudy and glorious palazzo-lined procession down the Grand Canal to the finish.

Team Toque: I have no idea how they finished but am certain they ate well.

Italians love nothing so much as traditions, and the success of the first Vogalonga, whether protest or party, had the makings of one. Thus it has been repeated every year since. Mine—held June 8th—was the 40th. I was ready for it, or so I thought.

I’d arrived in Venice three days early to allow for easing jetlag, picking up my bib (#631) at the registry and finding a berth for my kayak. My chrome-yellow Feathercraft Kahuna is a mere 15-footer, but finding an accessible berth in Venice is like finding free parking in Manhattan. The more so because the event has grown steadily over the decades, this year to 8,000 rowers and 2,300 boats from the U.S., all parts of Italy, and many other European nations, even the Orient.

That popularity means that nowadays Venetian craft are far outnumbered by what Italians call a vasto assortimento of eight-oared racing shells; 20-paddle dragon boats stroked to merciless drumbeats and hortatory bullhorn cries; single and double kayaks; a sampan; war canoes; the odd paddle boarder and UFOs (unidentifiable floating object). That diversity fosters even more. Many women now enter (there are several all-woman crews); all ages; all races. Rowers include ego-driven racers; bronzed fitness gods wielding paddles big as small trees; and whole families, some with pets. In short, come one, come all, even dilettanti like your correspondent, whose modest aim was to cross the finish line on the same day I started.

I should have been so lucky.

And it all started so well, too. Pepys-like I was ‘up early and about,’ and my Kahuna, sponsons inflated drum-tight, was equipped with map, Yak-Clip, Yak-Grips, mooring line, life vest, water, energy bars, sun block and other impedimenta. I’d scouted a superb route from berth to start line, from the top of the city to the bottom: seven turns down eight canals, the last of them debouching into the Grand Canal opposite the church of Santa Maria della Salute, whence the shindig would commence.

The sight before me was heart-lifting: hundreds upon hundreds of boats, boats of all shapes and sizes and colors—a veritable river of boats, all of them cheerfully getting in and out of one another’s way. Rowers gabbed and gossiped, listened (or not) to the mercifully brief speeches, sang ‘Viva Venezia’ and club anthems. They were divided between those thrilled to be back and virgins hardly able to believe where they were. Then came the near-sacred rite of the Alzaremi (Raise your oars). The command Alza remi! thundered from the loudspeakers and enough muscle-powered propulsion units arose to make the river of boats almost a forest.

Somewhere in there a cannon woofed, and we were off. What was that like? I yield the floor to a colleague covering for a Roman paper: ‘Two thousand three hundred rowboats, which until then calmly floated before St. Mark, as if by magic then moved together, their motion driven by thousands and thousands of oars raised and lowered to the rhythm of the dragon boats’ drums . . . . A scenario evocative of another era, a suggestion somewhere between post-modern barbarian horde and a medieval military parade.’

All too short a parade for me, however, and painful to boot. Passing St. Mark’s I felt twinges of the lower-back spasms I thought I’d conquered two months earlier. They were just nagging, though, and maybe they wouldn’t become insistent if I slowed down and used my self-inflating lumbar pillow; maybe I could at least finish the course. Yes, merely finish. Let the myth be here dispelled: the Vogalonga is absolutely not a race, no matter how often you hear otherwise. Staged entirely by volunteers, it is that much-loved phenomenon Italians call a manifestazione, a gathering that means, more or less, ‘we’re here; learn to like it.’ Yes, some rowers race the clock or their pals, and clubs may vie boat to boat, but only and always privately, without sanction or public recognition. All registrants receive the same souvenir tee-shirts, posters and numbered bibs before the start and all finishers receive identical certificates and medals.

My spasms quieted, but a new and worse threat soon showed. An evil soreness in my left calf, merely annoying at first, began to throb and finally climb. By the time it reached my hip I was struggling. I slowed again and let the fleet pass by. It hurt to move, really hurt, and the prospect before me was grim. I could either bail out now, mere minutes after the start, or try to tough it out only to succumb anyway, complete with being medevac’d out by helicopter from the middle of the lagoon. Or something equally newsworthy, photogenic and humiliating.

One of my goals in life is never to be the subject of the phrase ‘film at 11,’ so I bailed. A small canal hard by led to Isola San Pietro, near Venice’s tail. I’d scouted a berth there two days earlier and headed for it now. The few hundred yards took most of an hour. I gingerly pried myself out of the cockpit, limped to my apartment and fell into bed with a large dose of pain-killer. End of glory.

But not end of story.

After four or five hours of Hydrocodonal sleep, or coma, I awoke pain-free, and there was nothing for it but to spectate rather than participate. The best places for that are the Rialto and Accademia bridges over the Grand Canal, and especially the first bridge over the Canareggio. That’s where the great traffic jam occurs, usually caused by the coxed eights. These needle-narrow racing shells, 60 feet long and mounting four 12-foot oars or ‘sweeps’ on either side, are formidable obstacles to traffic flow. Mix one of two of those at the chokepoint with, say, a bulky pulling boat or two and some paddlers who, as Scarpa says, ‘do things that do not demonstrate a profound experience of boats,’ and there you are. Profanity and spectacle contend.

The first rower supposedly finished in a dubiously claimed 90 minutes; it had taken me that long just to quit. But if my Vogalonga was over, my paddling was not. I had three days left in Venice, all of them pain-free, so I devoted them to my master project, which is to paddle every inch of every canal in Venice and her islands. I’ve been working on it a few years now, and am halfway there. Thus I made several long passages along the northern side of the city, then went west to experience the city’s only traffic light. Halfway on I pulled over to Osteria da Simson, the local drive-thru: it offers canalside service. I traveled the Grand Canal end to end, which is perfectly safe if you keep your wits about you and stay well away from vaporetti at boat stops. (Especially never crowd the stern of a vaporetto; its propeller generates powerful vortices that will spin you like a top.) And then I consulted Scarpa, who has participated in every Vogalonga since Row One. Sage and sachem of Venetian rowing, teacher thereof and champion of many races, Paolo mused into his mustache and gave me three words: Vai da sera. Go by night.

Transiting the Grand Canal at midnight, with the Rialto Bridge ahead.

The next night I did. With a small LED flashlight taped to my deck for visibility’s sake I made a midnight transit of the Grand Canal. The density of daytime traffic on what Venetians call the Canalazzo might suggest that was suicidal, but not so. Venice is a sleepy-time gal, and in the late hours there’s almost no traffic at all. I spent hours, too, prowling the tomb-dark back canals, silent save for the paddle drips on my deck.

What was it like? I can’t say and won’t even try; it was an experience that calls forth the kind of adjectives beloved of hack travel writers, like ‘magical’ and ‘enchanting.’ If you want to know, then pack your bags and go. Spend a day or two paddling by day to build your confidence. Practice caution and discretion. Then, vai da sera.

IF YOU GO: Many websites give Vogalonga details, but the most reliable is www.vogalonga.net. Registration ($35) opens about March or April. Shorter and less intense are the guided kayak tours led by René Seindal, Marco Ballarin and Loretta Masiero. Minimum two persons, but singles can join larger groups: www.venicekayak.com.

The intrepid author displays his equipment.

GEAR: I use both Platypus and GoVino food-grade wine and water bottles; they fold flat when empty and don’t leak. I use a Hummingbird self-inflating pillow as a knee rest, but it was a godsend when I used it for its intended purpose: lumbar support. Dual AV-1 wraparound sunglasses are scratch-resistant and UVA/B proof, but their great appeal to near-sighted me, is their built-in, bifocal-style magnifiers (diopters 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 available). Now when I want to read a map, I can. (But next time, Dual, please polarize!) Night on the canals (and Venetian law) requires at least one white navigation light. A small LED flashlight will do but I’ve since discovered ball cap lights. Enter that in Google to find their infinite variety, many of them dirt cheap. They clip perfectly to my deck lines. Vibram FiveFingers are like anti-slip gloves for your feet, but they are tricky to put on and no good on pavement: when the globe is granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints, I prefer Crocs or similar footwear. I don’t use a paddle leash but prefer a Yak-Clip, which holds securely and releases easily. My mount is the Feathercraft Kahuna. Other folding kayaks are good, but none is so light as the speedy, nimble Kahuna, nor so easy to erect or able to fit into a single pack and squeeze under the airlines’ 50-pound limit. Inflatables are way cheaper but otherwise, to me, a poor choice: Many are heavier than folders; all are very beamy and so require extremely long paddles. Their characteristically high freeboard means they’re often bullied by winds, and absent a powered pump, they’re exhausting to inflate. Great guidebooks: Eyewitness Venice (Dorling Kindersley) and TimeOut Venice. A little night music for the canals: Mozart Adagios (K.622 can be used to prove the existence of God).

Kayaking the streets of Venice

WHAT IS VENETIAN ROWING?

It’s a unique style developed centuries ago by people whose lives and livelihoods depended on boats—and oars as the primary means of propulsion. The gondolier exemplifies Venetian rowing: He stands upright at the stern, facing the bow in a powerful stance (one foot a bit forward, he leans slightly into his oar). His oar rarely clears the water, seeming instead to swim alongside on the recovery stroke; his oddly shaped oarlock, called a forcola, assists in efficient, nimble rowing—forward, backward, even sideways —and he can always see where he’s going. There are variations. Some boats add a second rower, at the bow; another type has one rower but two oars that cross in front of him, so the left hand manipulates the starboard oar and the right hand the port. The Vogalonga has fostered perhaps even inflamed Venetians’ interest in their rowing tradition: there are now more than 40 clubs dedicated to it. Want to take an (expensive) lesson? Go to http://rowvenice.org/.

Text and photos ©2015 Bill Marsano