Text © 2014 by Lucy Gordan

Two years ago at a market stall near Vatican City I bought three illustrated cookbooks published only in Italian as supplements of the Italian magazine Famiglia Cristiana: La Cucina dei Pellegrini, La Cucina dei Papi, and La Cucina dei Santi (The Cuisine of Pilgrims, …Of Popes, …Of Saints). Part of an eight-volume series Enciclopedia del Mangiare Sano (Encyclopedia of Healthy Eating), three other volumes concern “religious” cuisine: vegetable and medicinal plant gardens, orchards, and cellars of abbeys and monasteries.

After reading in numerous sources that before his election Pope Francis customarily prepared all his own meals in his humble quarters near Buenos Aires’ cathedral and only occasionally ventured out to a nearby nunnery for his favorite dish bagna càuda, I became curious about Francis’ connection to this typically Piemontese specialty and the dish’s history, but also about his predecessors’ eating habits starting with St. Peter up to the Bavarian tastes of Benedict XVI.

Piemontese Immigration

According to the 190 Associations of Piemontesi in the World over 2,000,000 Piemontesi immigrated between 1870 and 1970 and now over 6,000,000 Piemontesi and their descendants live abroad. Argentina boasts the highest number of Piemontesi with 3,000,000; Brazil and the USA follow with 700,000 each. In the USA the majority live in California, Chicago and New York. Thus today immigrants of Piemontese descent outnumber their ancestral region’s 4,646,251 inhabitants.

One Piemontese immigrant to Argentina was Pope Francis’s father Mario José Bergoglio. According to María Elena Bergoglio, Pope Francis’s much younger (aged 66) and only surviving sibling (he had three others), Mario left Pontacomaro, a small farming town some 4 miles northeast of Asti, to escape Fascism when Mussolini rose to power in 1922. In Buenos Aires Mario married Regina María Sívori, born in Buenos Aires to a family of northern Italian (Piemontese and Genovese) origin. Mario was an accountant for the railways and Regina a housewife and mother.

Before he was Pope Francis, Jorge Mario Bergoglio enjoyed cooking simple meals at home in Buenos Aires.

Born in Flores, a barrio of Buenos Aires, their eldest child, Pope Francis, has always preferred the simple lifestyle. As I’ve just mentioned, even as Archbishop he lived in a small apartment near the cathedral, rather than in the elegant bishop’s residence in the suburb of Olivos. It’s also been well publicized that he took public transportation and cooked his own frugal meals of healthy foods: baked skinless chicken, vegetables, salads, and fruits accompanied by an occasional glass of wine. Once in a while he would break from eating alone to visit a convent where the nuns prepared bagna càuda, a sort of fondue with anchovies, garlic, olive oil, butter, sometimes cream, and a selection of pre-boiled autumn/winter vegetables: celery, sweet peppers, fennel, radishes, turnips, artichokes, cardoons, cauliflower, and onions, cut to bite-size pieces.

Bagna càuda is a dish typical of the cucina povera of Piemonte

A specialty of Italy’s Piedmont region during autumn/winter, especially immediately after the grape harvest and on Christmas Eve, the heartily-flavored bagna càuda or “hot bath or dip,” seldom found on restaurant menus outside the region until recently, is placed at the center of the table for communal and festive sharing and accompanied by Piemontesi reds: Nebbiolo or Barbera (especially a young one), and eggs to scramble in the leftover bagna càuda. The ingredients for 4 people: 4 fl oz. of extra virgin olive oil; 4-5 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed; 12 anchovies preserved in olive oil, drained and chopped; 4 oz. unsalted butter cut into cubes; cream to taste. Prepare: 1) Put the olive oil in a pan with the garlic and anchovies and stir over a low heat for a few minutes. 2) Whisk in 3½ oz. of the butter, and as soon as it has melted, remove the pan from the heat and whisk a few more times so that everything’s creamy and amalgamated. 3) Taste, and if you feel you want this dripping sauce a little more mellow, then whisk in two more tablespoons of butter or cream to taste (it’s meant to be pungent but not acrid). 4) Pour into a fondue dish over a flame or into a very warm bowl. 5) Serve with pre-boiled vegetables.

Babette’s Feast poster

Besides bagna càuda, Pope Francis’s other gastronomic preferences include strong coffee, “ristretto,” consumed at a bar counter, and mate, a traditional South-American, especially Argentine, caffeine-rich infused drink. Not surprisingly perhaps because of his disapproval of materialism, his favorite film is “Babette’s Feast,” based on Isak Dinesen’s (Karen Blixen) story.

Bagna Càuda’s Story

Bagna càuda is one of Piedmont’s most appreciated dishes along with brasato al Barolo, bollito (boiled meats), la finanziera (mixed innards), agnolotti (large meat-filled ravioli), Castelmagno cheese risotto, fonduta with shaved white truffles from Alba, fritto misto piemontese, and gianduja (chocolate with hazel nuts). But how did bagna càuda arrive in land-locked Piedmont since its main ingredients are sea-dwelling anchovies and olive oil, neither of which are native-sons of Piedmont?

Its origins are remote. Some sources say that the ancient Romans may have introduced it here and that it may be a direct descendant of their supreme condiment garum, a sauce derived from fermented fish. Others say that its arrival dates to the Middle Ages thanks to hard-working Piemontesi farmers with families to feed through the winter when only root crops and hardy stored greens such as cabbage were available. Luckily they had garlic, plenty of garlic, because Medieval statutes obligated every farmer to grow it. In fact, because of this predominant ingredient the upper classes long scorned bagna càuda.

However, this humble sauce probably has a more complex history of farming culture, regional commerce and tax evasion. While rich in garlic, grains, butter, cheese, and wool, Piedmont did not have anchovies or olive oil. These were obtained through barter probably with neighboring Liguria, where olive oil and fish were abundant and cheap, as was salt, although the Region of Piedmont’s website says the Piemontesi farmers traveled to Provence, not to Liguria, to barter, that the dish’s original name was “Anchoiade” and that its recipe was not mentioned in any Piemontese cookbooks until the novelist Roberto Sacchetti did so in 1875.

Salt was probably the first ingredient to make the mountainous trek from the Ligurian coast or Provence to Piedmont. It is still essential for human and animal health and was for food preservation in pre-refrigeration times. The Romans had built “salt roads” throughout their empire from the Mediterranean to Northern Europe. The industrious and hearty farmers of the Val Maira, a valley in the province of Cuneo in southern Piedmont, traveled regularly for trade through the Maritime Alps to Liguria or perhaps Provence on one of these “salt roads.” They loaded their mules with wheat, butter, cheese, oak barrels, and woolen goods on the way to the sea and on the way back with salt and fish. The precious salt was tightly controlled and heavily taxed so the story goes that the farmers would fill their barrels with contraband salt and then top them off with anchovies. If they were stopped and their cargo inspected, the officials only saw the tax-free anchovies. This story has a number of variants, but smuggled or not, anchovies and salt made their way up to Piedmont and into bagna càuda for hundreds of years. The first versions of bagna càuda were most likely made with the region’s rich walnut oil from the vast walnut groves that used to be found throughout Piedmont and in the Val d’Aosta. After large areas were deforested, olive oil, too, had to be imported. Although olive oil and butter now serve as the base for bagna càuda, it is still customary to add a few crushed, roasted walnuts to the sauce to remember its traditional flavor. Today bagna càuda is one of the best examples of “cucina povera,” the humble healthy dishes born of necessity and few ingredients. For memorable ones, head to Chef Carlo Bologna “Trattoria I Bologna,” Via Nicola Sardi 4, 14030 Rocchetta Tanaro (Asti), the nearby “Agriturismo Cascina Madonna,” Via Alessandria 55, 14030 Refrancore (Asti), or “Ristorante Valsangone,” Piazza Molines 43, 10094 Giaveno (Torino).

Papal Eating Habits before Pope Francis

John Dory, or St. Peter’s Fish

To return to papal gastronomy over the centuries, most of our information dates to the Middle Ages, Renaissance or from the 19th century onwards, but there are many of the now 266 popes for whom we have no culinary records. Here are the highlights of my discoveries.

St. Peter was a fisherman on the Sea of Galilee and its spiky little John Dory is also known as “Peter’s Fish.” According to the article, “What Popes Liked to Eat for the Last 2,000 Years,” in February 12, 2013’s Bon Appétit: “…the fish gained its pair of black spots through direct saintly intervention: one story says that Peter, seeing how ugly the fish was, picked it out of his net with his thumb and forefinger (making the marks) and tossed it back in the briny; another links it to Peter’s earlier past as a charcoal-maker; and yet another claims that he found a silver coin in the fish’s mouth, and that the marks are some kind of sign of gratitude.”

A bowl of cherries with plums and melon, by Louise Moillon, 1635

According to Mariangela Rinaldi and Mariangela Vicini’s Buon Appetito Santità (1998)(its text and recipes are probably the source of the above-mentioned books and article), St. Peter also liked lamb and corratella (innards). From Peter we jump to Gelasius I (492-96), who provided crespelle or pancakes to French pilgrims in Rome who took the recipe back to France, and then to Gregory the Great (590-605), who suffered cravings for cherries, although otherwise extremely frugal. A Latin inscription on an outdoor portal of the Aventine Basilica San Saba translates “from this house everyday my pious mother (St. Silvia) brings a bowl of vegetables to the Clivio di Scauro” (the monastery were Gregory lived)).

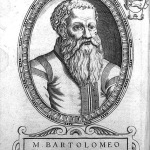

Bartolomeo Scappi, chef and cookbook author

Frugal popes before our Pope Francis include strict teetotaler Eugene IV (1431-1447), exclusively meat-eating Flemish Hadrian VI (1522-23), organic-foodie Sixtus V (1585-90), Innocent IX (1591), and bread-and-water fasters Clement VIII (1592-1605) and Clement IX (1667-69). Others are Sixtus IV (1471-1484), the founder of the Vatican Library, who compensated his overeating at official banquets with drastic starvation diets of vegetables, milk products, and codfish; the insomniac former Dominican Paul V (1559-65), the only Borghese pope, whose chef paradoxically was the super-talented Bartholomew Scappi, the author of the world-famous 900-page Opera dell’arte del cucinare; and his successor Pius V (1566-1562), who nourished himself almost exclusively on donkey’s milk. According to Bon Appétit, the latter “is described in the Oxford Companion to Italian Food as an ‘intransient ascetic who maintained an austere and abstemious attitude towards food and drink, and the table, for which he laid aside a miserly sum.’ When intensely weakened by constant fasting, he threatened to excommunicate anyone who would strengthen his daily broth.” Another pope who loved dairy products, especially cacio cheese made from ewe’s milk from his home village Pienza, was the Renaissance humanist Pius II Piccolomini (1458-64), famous for scholarship and his magnificently frescoed library in Siena (Entrance 3 euros, March 1-Nov. 2 10:30-19:00; Nov. 2-Feb. 28 10:30-17:30).

In contrast, the food-loving pontiffs began with Innocent III (1198-1216), one of the medieval Church’s most powerful popes, who had a predilection for Verdicchio wine, which he drank from golden goblets. Chronologically he’s followed by French-born Martin IV (1281-85), whom Dante placed in Purgatory because of his passion for eels from Lake Bolsena, which he himself cooked in “Vernaccia.” He’s said to have died from indigestion.

Pinturicchio’s fresco of Pius II leaving for the Council of Basel

A decade later Boniface VIII (1294-1301), who organized the first “Jubilee Year” in 1300, was another hedonistic pope. Not only was his goblet made of transparent precious stones, but all his tableware was solid gold. Since he declared that both spiritual and temporal power were under the pope’s jurisdiction thereby subordinating kings to the Roman pontiff, “understandably,” as Bon Appétit reports, “he was terrified of being poisoned, and not only employed a full-time food taster, but made semi-magical implements for the purpose, shaped like unicorn horns, saplings, or a snake’s forked tongue. He also ate with ‘magic knives,’ which were supposed to reveal poison on contact.”

Speaking of knives, Clement VI (1342-52), the 4th of seven Avignon popes (1309-77), all great wine lovers, announced that his aesthetic predecessors “did not know how to be pope” and hosted lavish 9-course feasts with over 30 dishes where only he was allowed to eat with a knife to safeguard against the outbreak of violence. Undoubtedly, his favorite local wine from Châteauneuf was a more reliable deterrent and thus gained the name “Châteauneuf-du-Pape.”

Again according to Bon Appétit, Martin V (1417-31), although upright and the peacekeeper of the “Great Schism” was another big eater. “His chef, the German-born Giovanni Bockenheym, wrote down 74 separate recipes [Registrum coquine, the first surviving document concerning the papal kitchen], each meant for the different social classes of people visiting the pope: spicy chicken soup for visiting kings down to bread and leek soup for lower level clergy. He even included an orange and cream dish meant for adulterers and harlots, intentionally designed to keep libido low.”

Melozzo da Forli’s fresco in the Vatican Museums of Sixtus IV appointing Platina Prefect

Another pope, art-loving gourmet Paul II (1464-71) was famous for reintroducing Carnival in 1468 and for his chef Bartolomeo Platina whom later, in 1477, Sixtus IV appointed the first Prefect of the Vatican Library. Platina’s cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine, was the first ever printed on a press. “Published in 1470,” recounts Bon Appétit, “it included an unfortunately prophetic section, warning of the dire consequences of eating melon on a full stomach, noting that they were best as an appetizer. Paul II died from eating ‘two good big melons’ poisoned or otherwise (reports are hazy) the next year.”

Speaking of poison, according to Oretta Zanini De Vita in her Popes, Peasants and Shepherds: Recipes and Lore from Rome and Lazio, Benedict X (1303-04) owed the brevity of his papacy to his passion for figs, also shared 300 years later by Urban VIII Barberini (1623-44). For on a visit to a Dominican monastery in Perugia, some conspirators took advantage of his weakness and served the medieval Holy Father a basket of beautiful fresh figs—filled with so much poison that he died within a few hours. Corrupt, nepotistic Alexander VI (1492-1503), possibly co-host with his son Cardinal Cesare Borgia of the infamous alleged orgy, Banquet of the Chestnuts, had a favorite family poison, “cantarella” nicknamed “the liquid of succession.” “Slow-acting, ‘cantarella’, Bon Appétit recounts, “was reportedly made by sprinkling pig entrails with pure arsenic. After some time, the entrails were then wrung out, resulting in a semi-organic, tasteless liquid that was a subtler and more effective killer than straight arsenic.”

The first two Medici popes, the obese and good-humored patron-of-the-arts Leo X (1513-1521) and Pius IV (1559-65), uncle of San Carlo Borromeo and presider of the last session of the Council of Trent, were both gourmands. While it’s rumored that once pleasure-loving Leo X, who liked to play practical jokes, decided to entertain his dinner guests by forcing his court fool to eat a leather jacket “stewed in savory sauce,” Pius IV liked to drink barley water and eat frogs fried with garlic and parsley according to his already-mentioned chef, Bartolomeo Scappi.

After Pius IV, who habitually took at least three hours over a meal of at least 20 courses, we have to jump ahead a few hundred years to Luddite Gregory XVI (1831-46) the next pope we know enjoyed his food. He liked to catch his own fish and travelled the countryside for days to taste local delicacies, but he also imposed a new tax on wine.

Instead the first pope of the 20th century, Leo XIII (1878-1903) and his successors: Pius X, Benedict XV, Pius XI, and Pius XII, for the next half-century harkened back to the asceticism of some of their distant predecessors. Leo XIII’s physician Dr. Lipponi once remarked, “ I eat more in one meal than the Pope does in seven days.”

Pope John XXIII

To the contrary, Pope John XXIII (1958-63), born into a large farming family near Bergamo and called “il papa buono” and “peasant pope,” loved home cooking and was a hearty eater. His favorite food was cornmeal polenta, homemade caseuola, and Taleggio, Robiola, and French cheese because he’d been Apostolic nuncio in France.

Pope John Paul II

Like John XXIII, Popes John Paul II (1978-2005) and Benedict XVI (2005-2013) loved the foods of their birthplaces. John Paul II’s favorites were kremowka, a “cream puff” from Wadowice, Poland, a buttered roll and glass of goat’s milk for breakfast, Polish meat for lunch, and Polish cold cuts for supper, all prepared by Polish nuns. Instead sweet-tooth Pope Benedict XVI’s gastronomic tastes were tied to his native Bavaria: Christmas cookies, beer particularly Franziskaner Weissbier, a light monk-made brew, and Bavarian potatoes with pancake strips.

A 1974 article in People Magazine reported that Paul VI (1963-78), whose meals were prepared by nuns from his hometown of Milan, liked “to unwind in the evening with a light scotch and soda,” that he often ate alone or with his secretary, his brother, and visiting cardinals. Much more importantly, however, for the 1.2 billion Roman Catholics around the world, in 1966 his Paenitemini reformed the rules on fasting and abstinence, allowing prayer and works of charity to substitute for deprivation especially in poor countries.