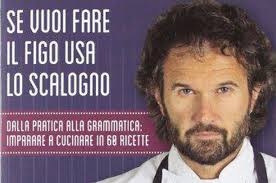

To celebrate 2015’s “World Environment Day” on June 3 the Rome-headquartered International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) partnered with Italian celebrity chef, Carlo Cracco, to bring attention to the negative impact of climate change on many traditional foods in developing countries. Famous for his truffle dishes at his two-Michelin-starred Milanese restaurant named “Cracco” after himself, last March chef Cracco, who’d recently published a new book, “If You Want to Show Off, Use Shallots,” visited the Highlands of Eastern Morocco for two days. (In February 2014 he’d opened a second, but simpler, bistro and cocktail bar, “Carlo e Camilla in segheria” in the trendy Milanese neighborhood “Navigli”).

Cracco toured sites where truffles once thrived. IFAD farming experts explained to him, a disciple of the world-famous chefs Gualtiero Marchesi, Alain Ducasse, and Annie Féolde as well as a judge of Italy’s TV program “Masterchef,” how overgrazing and climate change are contributing to land degradation, causing desertification, drought, and prolonged hot and cold weather. While there, Cracco starred in an episode of “Recipes for Change,” which shows him cooking a traditional lamb and truffle tagine with local small-scale farmer Fatima Abed.

“Coming here has been a humbling experience,” remarked Cracco, who’s certainly not known for his humility. “If you let it, the desert will continue to advance. Therefore it’s essential to help the people who live here to recuperate their land so they won’t be forced to move away. They need to become food secure again.”

Why don’t you try cooking Moroccan tagine with terfass and lamb. You can substitute the terfass with root vegetables such as parsnips, carrots, or potatoes.

This recipe serves 8. The ingredients and cooking instructions:

• 1Kg (2.2 pounds) lamb shoulder meat

• 2Kg (4.4 pounds) truffles (terfass)/alternatively use mixed root vegetables such as potato or parsnips

• 2 onions

• 4 finely chopped garlic cloves

• tbsp coriander

• tbsp parsley

• 3 tbsp olive oil

• tsp ginger

• tsp cinnamon

• ½ tsp saffron

• tsp cumin

• salt and pepper

• Cut lamb into pieces, brown with olive oil and onions in large pot.

• Once browned add garlic, herbs and spices and cook for 5 mins. Then add 1 litre of water.

• Cover and simmer on a low heat for 1 hour.

• Meanwhile wash terfass (or substituted root vegetables) thoroughly, peel and chop into big chunks. Cook in boiling salted water for 10-15 mins until tender.

• Remove from the water and fry with a little olive oil and water from the lamb for 5 mins or until golden brown.

• Add terfass 10 mins before the lamb is done. Serve with cous cous.

“In 2015 we at IFAD made six ‘Recipes for Change’ videos with five well-known chefs besides Cracco,” Brian Thomson, Communication and Advocacy Manager, told me in June. “All are aimed at a general audience and dubbed into English, French, Italian, and Spanish. We want to encourage people who consult our website, www.ifad.org, be they private individuals, small farmers or government officials, to join the ‘Recipes for Change’ community.”

If you Google ‘Recipes for Change’ and then click on each of the six individual case studies, you can read about the reasons for their threatened environments and IFAD’s interventions to help the local populations, watch the video, and home-test IFAD’s local recipe, some of the ingredients having been adapted to what is market available in developed countries. See the above example, where potatoes and parsnips have been substituted for truffles, which cost a fortune in the developed world.

“We plan to ask our ‘members’ to sign a petition asking the governments participating in the Climate Change Congress in Paris next December, to relegate more funds to help smallholder farmers in developing countries to adapt to climate change,” Thomson said. “We can’t stop climate change, but we can slow it down.”

Three videos besides Cracco’s were produced first. One stars 33-year-old Australian-born Bjorn Shen, a well-known chef from Singapore, where he is the owner of the Middle-Eastern inspired restaurant “Artichoke” and the author of Artichoke Recipes and Stories from Singapore’s Rebellious Kitchen. In November Shen is opening “Bird Bird House,” a 40-seat informal, inexpensive restaurant. It’s signature dishes will be Thai grilled chicken as well as what Shen calls “The Schwarzenegger of Som Tum” — an over-sized platter of green papaya salad with crispy chicken skin, salted eggs, fried anchovies, fermented rice vermicelli and fish crackers. For “Recipes for Change” Shen traveled to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, where the rising level of the sea is contaminating the river’s fresh water and killing off its freshwater shrimp and catfish.

Another video films Ali Mandhry, age 27, considered one of Africa’s top chefs, cooking Ibitoke na Ibishimbo (bananas with kidney beans and split greens) in Rwanda where increasing temperatures have damaged its two cropping seasons of sorghum, bananas, beans, sweet potatoes, and cassava. Born and raised in Mombasa, Mandhry, whose grandfather transmitted his love for preparing cakes, is the star chef on Kenyan TV of the weekly program, “Tamu Tamu: Kenyan Cuisine with a Twist.” In 2013 Africa Style Daily named him one of the five top chefs of African cuisine. The third shows Bolivian chef Marco Bonifaz, owner of “Flanigan’s Cave Gourmet“ in La Paz, in his home country, where the some 700 varieties of potatoes are under threat from rising temperatures and changing growing seasons. His dish here is “Chairo,” a typically Andean potato-based dish.

The next two videos show prize-winning chef Ska Moteane, who won Gourmand’s 2012 award of Best African Cookbook, in her home country of Lesotho cooking “Sechu Sa Nka” (Mutton Stew) and TV chef Ba Alpine from Senegal also in her home country preparing “Poulet Yassa.” Rising temperatures and frequent droughts threaten Lesotho’s economy, dominated by livestock production and its export of wool and mohair. In Senegal rising sea levels have increased the salt level in the soil and erratic rainfall and weather patterns are making it increasingly difficult to farm Senegal’s staples: rice and onions.