The Parmalat scandal must not steal the limelight. A byword for fine food and good living since the Middle Ages, Parma and environs, known as “food valley,” had only shortly before received the gastronomic recognition it clearly deserves. After a 2-year tug-of-war and carefully orchestrated negotiations, on December 13, the European Union finally appointed Parma its European Food Authority over Barcelona and Helsinki. Secondly, as he sneak-previewed in his Q & A in the present issue of Epicurean-Traveler.com, Gualtiero Marchesi will be rettore magnifico of ALMA , the first and unique program of a “Master of Italian Cuisine,? which started its classes in January 2004 in the magnificent “Palazzo Ducale” in Colorno (about 10 km. north of Parma). Last but not least, on November 29, 2003, in Soragna (27 km. northwest of Parma) the Museum of Parmesan, an edible, completely handmade work-of-art, was inaugurated.

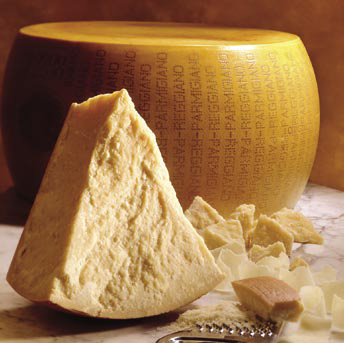

Housed in the only surviving mid-19th century round “casello” of the cheese works once owned by the Prince Meli Lupi, the museum has three rooms. In the first the various production phases–only between April 15 and November 15, when the animal feed (mixed grasses and clover) is at its best and the milk at its richest–are explained through the display of equipment and hundreds of utensils (some extinct) necessary for hand-making (never manufacturing) and distributing this “king of cheese;” an 18th-century copper cauldron, an old milk wagon that was pulled by hand, an early steam boiler to heat the milk in the cauldron uniformly, and an early 20th-century churn, to name a few.

Salting prosciutto hams

In the second called “Sala della Salamoia” or “Curing or Salting Room” are panels illustrating the history of Parmesan ? a very old cheese. Parmesan, mentioned by Columella, Varro, and Martial, seems to go back to ancient Roman times, but the first surviving historical documents date to Parma’s Abbey of S. Martino dei Bocci in the late 1290s. At first the wheels were only 3.2 inches high in contrast with the 10 inches of today because they were then covered with salt instead of immersed in salt water. Boccaccio’s Decameron (1348-49) boasts its first literary reference: in the third story of the eighth day, the poet poked fun at the gullibility of Calandrino, one of his characters, by having him believe that in Bengodi, in Parmesan country, there was a mountain consisting entirely of grated cheese and that the people who lived there did nothing but cook macaroni and ravioli which they rolled down the slopes so that the pasta arrived at the bottom coated with fragrant cheese. Parmesan’s first artistic representations are an 1693 engraving of cheesemongers by Bolognese Giuseppe Mitelli and an oil painting of cooks grating it by Luigi Crespi (1709-79), also Bolognese, while the first complete photographic sequence of parmesan production was shot by a German war correspondent in 1944.

The third room, ” Sala del Latte ” or “Milk Room” is devoted to the ageing process–at least two years ( vecchio or old), better yet three ( stravecchio or very old), and preferably four ( stravecchione or the oldest), though a wheel can keep for as long as 20 years, getting better with age–and to the history of the Consorzio or producers’ co-operative. The latest statistics dating to 2002 counted 547 members who relied on 270,000 cows belonging to 7,000 farmers for their milk: annually c. 409,425,000 gallons to make 245,691,904 pounds of cheese, for a total of 2,937,535 wheels. In 2002 production was up from 2,877,883 wheels in 2001 and 2,851,918 wheels in 2000. Between 88-90% of these wheels are eaten in Italy. An average of 90,000 wheels are exported every year to the USA. To produce a pound of parmesan it takes 2 gallons of milk and each wheel weighs an average of 66 pounds.

After your visit enjoy Soragna’s excellent hospitality and local cuisine. At the old-fashioned osteria Ardegna (Frazione Diolo, Via Maestra 6, tel. 011-39-0524-599337, closed Tuesday evenings, Wednesday, and July) the local salumi , parsley tortelli , the green ravioli stuffed with potato or with bacon and braised beef, the boneless guinea hen stuffed with asparagusare all to-die-for. At the small and homey Stella D’Oro with a few rooms for rent and one Michelin star (Via Mazzini 8, tel. 011-39-0524-597122, closed Monday, reservations recommended) try the local salumi , the elegant saccottino (little bag) of fresh goat’s cheese with stewed pears, the fig gelatine with accacia honey, or the roast shrimp with a leak omelette for starters; the traditional parsleyed anolini or tortellini, yellow and red pasta strips with a goat’s cheese, tomato and basil sauce, followed by “twice-cooked” quail or cod with an onion and tomato topping. The elegant Charme & Relax Locanda del Lupo (Via Garibaldi 64, tel. 011-39-0524-597100, www.locandadellupo.com, closed 23-28 December), which began as post house in 1738, offers spacious rooms with antique furniture, a congress center, and a romantic restaurant with two fixed-price menus. Of special note are: rabbit with almonds in spinach broth with crispy bacon and taglierini with prosciutto and black truffles.

The Museum of Parmesan is open on weekends and by appointment. The Entrance fee of 5 euros includes a tasting. For information: tel. 011-39-0521-228152 or www.museidelcibo.it.

A bonus: The Parmesan Museum is only the first of three food museums to be opened near Parma in the near future: the Museum of Prosciutto and Local Pork Products (salami di felino, Culatello di Zibello, la Coppa e la Spalla di San Secondo) is scheduled to open in Langhirano’s ancient Roman Forum Boarium or meat market in March 2004 and the Museum of the Tomato in the Renaissance Corte di Giarola in Collecchio during 2005.