Pesto

In the late spring little pots of the culinary herb basil (basilico in Italian) go on sale at flower stands and market stalls all over Italy. Placed on terraces and balconies chefs and housewives add hand-picked leaves to their summer dishes for color, fragrance, and anise-like flavor.

Originally a native of India and tropical regions of Africa and Southeast Asia, today basil is used in cuisines worldwide. For examples, the Chinese and Taiwanese use fresh or dried basil in soups. They also eat fried chicken with deep-fried basil leaves. In Thailand basil is commonly steeped in cream or milk to create an interesting flavor in ice cream or chocolates.

Basil is particularly popular in Italy, where I live, especially in Genoa, where it’s profusely cultivated on terrace farms close to the city. Basil is the main ingredient of pesto, a pasta sauce of crushed (pesto in Italian) basil leaves, pine nuts, garlic, Parmesan cheese and olive oil. It also features prominently in the southern Italian dishes pomodori al riso (baked tomatoes filled with rice) and insalata Caprese of mozzarella cheese slices, tomatoes, and basil leaves named for the world-famous island of Capri where it was first served. Just across the Bay in Naples, the pizza Margherita’s toppings have the same ingredients.

A legend recounts that on November 6, 1889 the pizzaiolo Raffaele Esposito, Pizzeria Brandi’s chef, invented this pizza in honor of the Queen of Italy, Margherita of Savoy, during her visit to Naples. He supposedly chose the toppings to represent the colors of the Italian national flag. While the pizza Margherita undoubtedly became more popular after the royal visit, a book by “a certain” Riccio, otherwise unknown, entitled Napoli, contorni e dintorni (Naples, side-dishes and surroundings) (1830) had already described a similar pizza as had Emanuele Rocco in 1849, but here the slices of mozzarella and the basil leaves were arranged on the tomato paste in a flower shape because Margherita means “daisy” in Italian.

Pizza Margherita

In addition to its culinary connection, basil is an efficient insect repellent and is associated with many rituals. The French sometimes call basil “l’herbe royal”; Jewish folklore suggests it adds strength during fasting. In Portugal a future groom traditionally gives a pot of basil, a love poem and a paper carnation, to his fiancée on the feast days of St. John and of St. Anthony. On the contrary, in ancient Greece basil was the symbol of hatred.

Basil also has had a long religious significance. In ancient Egypt, ancient Greece and medieval Europe it was placed in the hands of the dead to ensure a safe journey to eternal life. Today it’s highly revered in Hinduism. In the Greek Orthodox Church it’s used to sprinkle holy water, while the Bulgarian, Serbian, Macedonian and Romanian Orthodox Churches prepare holy water with it and pots of the plant often decorate their church altars. Some Greek Orthodox Christians avoid eating basil because of its association with the legend of the Elevation of the Holy Cross, celebrated on September 14. For, according to Orthodox teachings, St. Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine the Great, discovered the Holy Cross on September 14, 325 AD near Golgotha, where it had laid in the dust for centuries. In the same place she also discovered a hitherto unknown plant of rare beauty and fragrance namely basil.

St. Helena’s red porphyry sarcophagus in the Vatican Museums. Because of its military scenes, it was probably made either for her husband or her son.

Portrait of St. Helena by Veronese in the Vatican Museums. She is dreaming of where she will find the True Cross

Its name probably derives from the Greek basileus meaning king maybe because the plant was used in he production of royal perfumes. Another explanation is that its name has been confused in Latin with basilisk, as

it was supposed to be an antidote to the basilisk’s venom. In zoology bright green basilisks are members of the lizard family, which also includes iguanas. It is sometime known as the “Jesus Christ lizard”, and lives in the forested areas of Central America.

Green Basilisk in Costa Rica

Mentioned in ancient Greek legends and medieval bestiaries, the basilisk is also a mythical reptile, a giant serpent, also known as “King of he Serpents”. It had lethal breath and gaze, which could petrify or kill if you looked at it directly in its bright yellow eyes.

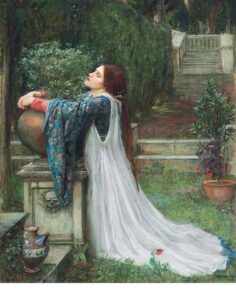

To return to the plant, many centuries later after St. Helena’s discovery, basil was featured in literature and art. In the Decameron, a collection of 100 short stories written in c. 1350 by Giovanni Boccaccio, the Tuscan poet and writer, for ten of his friends secluded in a villa outside Florence during the Black Death, in the fifth story of the narrative’s fourth day a pot of basil is central to the plot: Elisabetta’s family want her to marry a prosperous nobleman, but she is in love with Lorenzo, her three cloth merchant brothers’ accountant. After her brothers murder Lorenzo and bury his body, he appears to Elisabetta, also known as Isabella, in a dream and tells her where he’s buried. Broken-hearted, she exhumes his body and buries his head in a pot of basil, which she tends obsessively. When her brothers confiscate her pot, she dies shortly thereafter.

Portrait of Keats by William Hilton

Boccaccio by Andrea del Castagno

Boccaccio’s story inspired the British poet John Keats (1795-1821) to write in 1818 a long narrative poem entitled Isabella, or the Pot of Basil. In turn, Keats’s poem inspired three paintings of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: John Everett Millais’s Isabella in 1849, today in Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, and William Holman Hunt’s and John William Waterhouse’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil (both 1868), today both in the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Later John White Alexander depicted the poem in his 1897 Isabella and the Pot of Basil, currently in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

William Holman Hart’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil

Waterhouse’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil

Wonderfully informative! Thank you.