Thomas Jefferson with wine glass

On a family vacation in c. 1990 to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s 5,000-acre plantation near Charlottesville, Virginia, I visited his house, his vegetable garden and his vineyards, the first ones in the United States, although his repeated attempts to plant various European grape varieties were unsuccessful. Then several years later in 2008, I went on a press trip to Vercelli, Italy’s rice-producing province in Piemonte, which Jefferson had visited in 1784 while Minister to France (1784-89). There I learned not only that he had a weakness for the local red wine “Gattinara” made from the Nebbiolo grape since Roman times, but also that he’d “risked the death penalty when he smuggled out some rice plants from Vercelli to Monticello. He wrote later in a letter (now among the Jefferson’s Papers in the Library of Congress) that the quality of his rice crop from Piedmont was superior to any he knew” (My “Off the Beaten Path in Piedmont, Epicurean-Traveler.com and “Vercelli: Of Rice, Old Books, and Varallo’s Sacred Mountain”, Inside the Vatican, both August 2008).

Therefore it did not come as a total surprise when I read about Jefferson’s love of wine and about the account book of his wine collection in a blurb published in www.winenews.it‘s column “Focus” on May 11. “Of all the American presidents,” it reported, “no one loved wine as much as Thomas Jefferson, and now we know which ones he loved to drink. The New York Public Library, in fact, has digitalized all the documents it houses that belonged to this American president, including a small brown leather notebook of lists in which Jefferson had recorded all his purchases of wine from 1791 to 1803. Jefferson’s lists in tiny precise script are very detailed; for example, between March 4, 1802 and March 4, 1803 Jefferson spent $1,296.63 on wine. A large amount of money for those times, it included wine for his personal consumption and that which he offered to his guests at The White House. Some of his purchases stand out: 100 bottles of Champagne for $172.50, 360 bottles of “Sauterne”, Sherry, Bordeaux, Chambertin, and surprisingly, 138 bottles of Italian wine “from Florence” including 123 bottles of Nobile from Montepulciano. This is particularly noteworthy since during these times Italian wines were seldom appreciated in British and American High society, which preferred French and Portuguese wines. Among the highlights are 400 bottles of Champagne from Aÿ and 36 of Bordeaux’s Château Margaux 1798.”

The Italian website cited its source as a lengthier article, “Thomas Jefferson—Lover of Wines, Keeper of Records” by Lettie Teague, published the day before on May 10th, in the Wall Street Journal. “The account book,” Teague recounts, “normally rests in a temperature-controlled environment below ground in the library’s main branch on Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street…It isn’t on display and is only available to researchers.”

Thomas Jefferson’s wine account book

Another oenophile US President was George Washington, who, according to www.wineamerica.org “reportedly spent $6,000 on alcohol in a period of seven months between 1775 and 1776. Most of it on his beloved Madeira…Interestingly enough, Madeira wine played an incredibly large role in the early history of the United States. The 13 colonies were incapable of growing wine quality grapes so they looked towards imports, particularly Madeira, to meet their alcohol needs. Fortified with spirits and treated at unusually high temperatures, Madeira wine managed to survive the long voyage to the Americas without spoiling. In fact, Madeira was so beloved that the Founding Fathers used 50 bottles of it to toast the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This accompanied another 60 bottles of Claret and 22 bottles of port, quite the party for 56 delegates.”

Still other US Presidents who loved wine were James Buchanan, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan. According to www.blog.personalwine.com, “Like Thomas Jefferson, President from 1801 to 1809, President James Buchanan, President from 1857-61, was notorious for how much wine he purchased. At one time, his annual budget for wine was $3,000. That’s almost $80,000 in today’s dollars!…He was also known for his incredible capacity to drink. He once consumed 16 toasts on the Fourth of July alone.” Nixon was the first president to serve Californian wine to his guests at the White House, while his aides poured for him alone expensive Château Magaux, like Thomas Jefferson his personal favorite. Instead Ronald Reagan was a Californian to the core, even when it came to his taste in wine. Again according to www.wineamerica.org, at the White House “not only did he exclusively serve American sparkling wine in lieu of Champagne, but he was the first president to ever serve a Zinfandel at an official event. His love of California wine was so great in fact, that upon moving to Washington D.C., he sent himself a private supply of wine from Beaulieu Vineyards, Sterling, and Stag’s Leap.” For a complete list of US Presidents’ favorite drinks read “Mint Juleps with Teddy Roosevelt: a Complete History of Presidential Drinking” by Mark Will-Weber ((Regnery, 2014).

To return to Jefferson (1743-1826), besides being an oenophile, diplomat, and politician, he was a farmer, obsessed with new crops, soil conditions, garden design, and scientific agricultural techniques, a horticulturalist and a foodie. Jefferson’s culinary preferences were certainly refined during his years as Minister to France, but even before his time abroad, Jefferson had arranged for a French chef in Annapolis, Maryland, to train one of his slaves. Then on learning of his diplomatic appointment, he decided to bring his slave James Hemings with him to study “the art of cookery”. In her article, “Thomas Jefferson: American’s Pioneering Gourmand” published on www.history.com(/news/hungry-history/thomas-jefferson on July 3, 2014, Laura Schumm tells us: “Under the tutelage of a few well-known chefs and caterers, Hemings soon acquired the skills necessary to assume the role of chef de cuisine at Jefferson’s private residence on the Champs-Elysées, where Jefferson maintained a garden that included Indian corn from American seeds, along with other fruits and vegetables. The scientific gardener enjoyed exchanging plants with his French companions and experimenting with the most unusual vegetables he could obtain.”

James Hemings

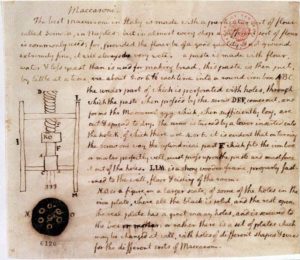

Like many a traveler returning home, Jefferson missed the dishes he had become accustomed to in France so he shipped 680 bottles of wine and, as www.foodtimeline.org tells us, “to his valet returning after him he sent a request for him to ‘bring a stock of macaroni, Parmesan cheese, figs of Marseilles…raisins, almonds, mustard…vinegar, olive oil, and anchovies.’“

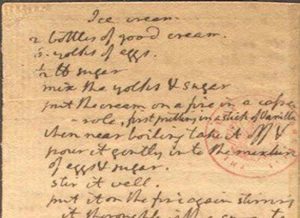

Jefferson’s ice cream recipe

Speaking of macaroni, it is one of the foods Jefferson is said to have introduced or made popular in the United States. The others are ice cream, French fries, waffles, and Parmesan cheese. To ensure that he could enjoy them for the rest of his life, Jefferson, who, while in France and northern Italy, had taken careful notes and drafted detailed sketches of local farming techniques and tools as well as cooking methods and utensils, also brought home with him several recipes (eight in his own hand are conserved in the Library of Congress) a waffle iron, a pasta-making machine, a steam-powered cheese grater, and ice cream freezer. It could be said that he was the first kitchen gadget enthusiast in America!

Jefferson’s explanation of how to make pasta

Although we don’t have his recipes, www.foodtimeline.org tells us “President Jefferson was particularly addicted to intricate dishes and brought back from Paris …his bouilli, daubes, ragouts, gateaux, soufflés, ices, sauces, and wine cookery…Jefferson confessed a preference for French cooking “because the meats were more tender”…He was especially fond of fresh vegetables and kept a careful chart of the season when certain ones would be available in the local market…[All this probably explains why he hired a maître d’hôtel, Étienne Lemaire, and a chef from France, Honoré Julien, to manage provisions and food preparation while he was in the White House]…A gourmet…Jefferson ate lightly…He preferred vegetables to meats and was particularly fond of olives, figs, mulberries,…oysters, partridge, venison, and pineapple…Yet despite his fondness for French cookery, Jefferson retained his liking for sweet potatoes, turnip greens, baked shad, Virginia ham, green peas, soft-shell crabs, and other American delicacies.”

Monticello

After his retirement from politics to Monticello, Schumm writes: “It was his experimental kitchen garden at Monticello that gave Jefferson the ultimate satisfaction. Cultivating 330 varieties of 89 species of vegetables and herbs, including more than 30 varieties of his all time favorite, peas, and 170 varieties of fruits while emphasizing the importance of fostering rich soil through organic matter, Jefferson was determined to introduce new crops that might help American farmers prosper and expand the country’s palate. Although his horticultural diary (1766-1824), ‘Garden Book’, details numerous failures, Jefferson wrote of his retirement: ‘I am constantly in my garden or farm, as exclusively employed out of doors as I was within doors when at Washington, I find myself infinitely happier in my new mode of life.’”