It is impossible to feel lukewarm about Venice. The historian Edward Gibbon, author of The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, complained about “its stinking ditches dignified with the pompous denomination of canals, while novelist D.H. Lawrence called her an “abhorrent, green, slippery city”. In fact over the centuries, luminaries, such as Dante, Goethe, Byron, Browning, Dickens, Monet, Renoir, Whistler, and Woody Allen (not to mention both Churchill and Hitler), have fallen in love with La Serenissima, as Venice is affectionately called. And bound to the city in both its history and in the hearts of its admirers is the gondola and its oarsmen, known as gondoliers.

It is impossible to feel lukewarm about Venice. The historian Edward Gibbon, author of The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, complained about “its stinking ditches dignified with the pompous denomination of canals, while novelist D.H. Lawrence called her an “abhorrent, green, slippery city”. In fact over the centuries, luminaries, such as Dante, Goethe, Byron, Browning, Dickens, Monet, Renoir, Whistler, and Woody Allen (not to mention both Churchill and Hitler), have fallen in love with La Serenissima, as Venice is affectionately called. And bound to the city in both its history and in the hearts of its admirers is the gondola and its oarsmen, known as gondoliers.

The gondolier is a thousand-year-old profession that personifies the magic, charm, and romance of Venice. Yet like many other historical and traditional professions in Italy (see SOS Italy’s Cheese), it is at risk. In order to safeguard the “Venetianess” of the tradition and the artisanship of the gondolier and his gondola, on September 3 the Gondoliers of Venice Association, founded in 2012, officialized its deal with “Emilio Ceccato”, a fourth generation Venetian clothing brand, to create a logo that will guarantee the originality and “Venetianess” of the uniforms of Venice’s 433 gondoliers. “Ceccato”, originally only a men’s shirt fabric shop, since 1902 has always been located near the Rialto Bridge at Sottoportico di Rialto, San Polo 16/17, tel. 011-39-041-5222700.

“Although many gondoliers customarily already bought their work clothes from “Emilio Ceccato” and the Sumptuary Laws of 1630 had stipulated that the gondoliers’ livery must be ‘cloth garments with a single row of buttons down the trousers’”, Chiara Lazzarin of the press office of Adnkronos Nord-Est told me, “but they did not have a uniform. Starting in November “Emilio Ceccato”, part of the Al Duca Dd’Aosta Group, will provide gratis one full uniform a year to each gondolier. Each piece of clothing will be branded with the new logo.

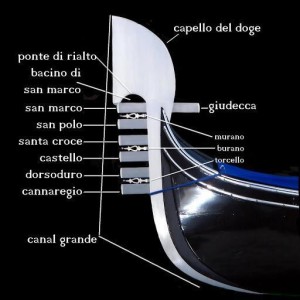

The round logo or trademark includes all the symbols of Venice and its history: the winged lion (Leone Marciana) an the open book, a symbol of peace, pride, knowledge and wisdom as well as St. Mark the evangelist, whose spirituality is symbolized by the lion’s wings and halo; the banner of the Serenissima Republic; the iron prow-head (“ferro da prua”), the top of which represents the Doge’s hat, while its comb-like prongs the six different neighborhoods of the city (called “Sestieri”). The prow-head facing backwards represents the Giudecca island and the little arch above the first “comb” tooth is a symbol of the Rialto Bridge. The iron prow-head has an “S” shape symbolic of the twists in the Grand Canal.

“Ceccato”’s gondolier uniforms will also be available for sale to the general public beginning in December at any of Al Duca d’Aosta’s eleven stores in Italy or online in Italy or from abroad at www.alducadaosta.com or from the recently set-up website www.emilioceccato.com. The prices are approximately: for the t-shirt or polo from 34 to 39 euros each; the sweatshirt from 59 to 69 euros; the cashmere sweaters c. 119 euros, and the Panama straw hat also c. 119 euros.

The proceeds from the retail sales will be reinvested in specific projects “to safeguard the traditions and the profession of the gondolier,” explains Lazzarin’s press release. “The projects include: implementing insurance policies for tourist protection, the increase of training courses for gondoliers, financial support for the safeguard of craftsmanship in the traditional gondola boatyards (called ‘squeri’), their Master wood craftsmen, (called ‘maestri d’ascia’-master of the axe) and ‘remer’, who craft oars and oarlocks (called ‘forcole’), training programs for new and young professionals to support ‘senior’ craftsmen and gondola docks (called ‘stazzi’ and ‘pontili’) maintenance.” The eleven “stazzi”, comparable to taxi stands, are located at Rialto, Bacino Orseolo, Danieli, Dogana, Ferrovia, Piazzale Roma, Santa Maria del Giglio, San Marco, Santa Sofia, San Tomà, and Trinità.

According to local legend, gondoliers are born with webbed feet, which help them to walk on water. But what is certain is a gondolier passes his intimate knowledge of the city’s waterways down from father to son (there has never been a female gondolier because of the strength necessarily involved in rowing, although young women do compete against each other in races. In fact, in the past the profession was commonly passed from father to son. It’s less so today because there are schools for training aspiring gondoliers, Enrica Marrese of Adnkronos Nord Est told me. “They must be over 18 years-old and study a foreign language, Venetian history, and Venetian art history as well as the practical requirements of rowing a gondola. They have to pass an exam open to the public and organized by the Ente Gondola. If they pass, they can enroll in the gondoliers’ professional register. Nonetheless they have to train for six months to a year with professional gondolier and then pass a “driving” test which is held when there is high tide or especially heavy traffic.”

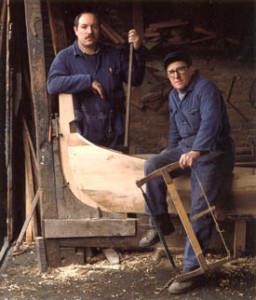

At the height of the Venetian Republic in the 15th and 16th centuries, more than 15,000 gondolas graced the city’s 177 canals, as many as six bobbling elegantly outside the homes of important families. However, today there are little more than 300 left for public use. Although many have scoffed at the suggestions of making plastic gondolas, there has been talk of making far simpler, cheaper boats. For it takes two craftsmen between 40 and 45 days (around 500 working hours) to build one gondola, at a cost of some $30,000, without trims and furnishings.

Two of the four remaining squeri are located close together in the sestiere Dorsoduro. The two others, Roberto Dei Rossi and Franco Crea are on the Giudecca. The easiest to find and the most picturesque at Dorsoduro, Rio San Trovaso 1097 is the Tyrolian-looking Squero San Trovaso of wooden structures, which dates back to the 17th century. Located next to the church of San Trovaso, it works predominantly on maintenance and repair, but occasionally builds a new one, which takes some 40 to 45 working days. It is possible to book a tour by telephoning to 011-39-041-522-9146 or better still by e-mailing a request to info@squerosantrovaso.com.

From here to reach the Squero Domenico Tramontin & Figli at Dorsoduro 1542, continue down Fondamenta Meraviglie to the wide Giudecca Canal. Turn right, over the bride across Rio San Trovaso, then take your first right. The street will dogleg then across another cnal. Turn left immediately to follow this canal along Fondamenta Bonini. Cross another side canal as you continue straight until the canal you’ve b

een following suddenly turns right to become Rio Sant’Avogaria. On the bridge that crosses this canal, look to your right and on the left side of the canal is Squero Domeco Tramontin & Figli, founded on February 2, 1884 (www.tramontingondola.it). Here sonless Roberto, the fourth generation and last member of his family after Domenico, Giovanni, and Nedis to craft gondolas, an exclusively male trade, carries on the family tradition with a non-blood-related associate. Here too it’s possible to book an hour-long tour for 3 to 30 people for 100 euros by telephoning to 011-39-041-5237762.

Roberto, world-famous, like his family-members before him, for their elaborately decorated gondolas, uses no sketches, diagrams, or prefabricated parts. Instead, he keeps the knowledge of how to season, cut, fit, and assemble a gondola’s 280 pieces of nine different woods in his head.

“Although the design of the gondola has changed over the years, the bottom has always been made of Austrian fir because of its lightness and durability,” Roberto told me. “Its ribs are made from elm because of their elasticity, and the sides of oak. All five transverse pieces are made of cherry because it bends so easily.” The top part, where the gondolier stands, is made of larch because it lasts a long time. Mahogany is used for the top carved section, and lime for the center, since this type of wood does not expand or contract much.

Roberto also told me that he can make any gondola longer, wider, or higher, but he cannot change the black color decreed by the 1562 Sumptuary Laws, which were passed to crack down on potentially destabilizing displays of personal wealth. Before then, gondolas used to be lavishly decorated with gold and painted in a range of colors.

“A gondola is at her prime at seven years old,” he chuckled. Then she is like a woman of 35, polished, well-curved, and settled into herself.”

“It takes 10 to 15 years to learn how to build a gondola properly,” continued Roberto. “The city’s worsening pollution and increased motorboat chop have reduced the lifespan of a gondola from 30 to 15 years. With only four squeri left, we can only build a total of 10 to 12 new gondolas a year. Unfortunately, that’s not enough to maintain the current fleet.”

The gondola is one of the few watercraft built to be asymmetrical. The left side where the gondolier stands is 9.5 inches wider than the right, where the oar plows the water. Its rakish list to starboard is purposely designed to make it rowable by a single gondolier, who stands upright and pushes on the oar to row the boat in the direction he is facing. For without the leftward curve the gondola would go around in circles.

Flat-bottomed and with no keel, the gondola is propelled at four kilometers per hour by one steersman using a 14-foot oar. And although it weighs half a ton (with the gondolier), it can take on six passengers, lots of cushions, a vase of artificial flowers, and the gondolier’s lunch. It is 36 feet long, about five feet wide in the middle, and slender enough to make 90-degree turns with ease. Despite its apparent fragility, a gondola is virtually unsinkable.

Exactly when this quietly majestic boat was born nobody knows, but some form of the gondola emerged shortly after the mid-fifth century, when mainland dwellers living at the head of the Adriatic Sea in northeastern Italy were forced to flee from the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Huns, to small islands across the limpid waters of Venice’s lagoon. Here the refugees hammered piles into the mud, building their new homes in places that the invaders would find difficult to reach. To travel among the 118 islands of Venice, the Venetians developed a lightweight watercraft.

The first reference to this unique boat dates to 1094 when doge Vitale Falier assigned to the “esteemed inhabitants” of Loreto the task of building him a gondulam. Some historians say that the word derives from the Greek or Latin for “shell concula”, but there is also evidence that the craft was first called a cymbula, meaning “skiff”. However, the late British etymologist Eric Partridge believed the word originated from gondolare, Venetian for “to undulate”, or perhaps from a corruption of dondolare, meaning “to rock or to swing”.

Before or after your tour of either squero, drop in to Osteria Al Squero at Dorsoduro 943-944 just across the canal from the San Trovaso squero, for a prosecco (sparkling white wine) or a spritz accompanied by a wide choice or cicchetti, Venetian tapas or snacks, considered the best in town, at fair prices. TripAdvisor rates Al Squero No. 7 of Venice’s 1,217 restaurants. It’s open all day.

Also close-by and for a more substantial meal at Dorsoduro 366 is Ai Gondolieri, a refined, wood-paneled, and Michelin-and- Zagat-admired oasis. Once an osteria frequented by gondoliers, hence its name, since the 1980s it’s been a place for a treat! Among its regular clients are Carla Fracci, Valentino, Elton John, Tom Cruise, Hugh Grant, Woody Allen, and Frank Gehry. Also near the Guggenheim Foundation and the Accademia, a place where you can hear yourself think, it’s a quiet and pleasant change amid the city’s mostly clattery, tourist trap dives. Its menu is surprisingly fishless because it’s deeply rooted to the culinary traditions of the Veneto’s mainland: venison, duck, pork, and cheese. It’s also strong on vegetarian dishes. Try the delicious multi-course tasting menu. It’s a bargain at 65 euros. Excellent wine list.

For a first-hand experience Nota Bene: Once essential for the transport of goods, gondolas are used only by tourists (apart from Venetians on their wedding day).

Before boarding, check the official tariffs. For 40 minutes and up to six people from 8 AM to 7 PM a ride costs 80 euros. Add 40 euros for an extra 20 minutes. From 7 PM to 8 AM for 40 minutes and up to six people a ride costs 100 euros. Add 50 euros for an extra 20 minutes.