Alliteration conjures treasures in the Veneto. Venice, Verona, Vicenza come readily to mind, and a fourth joins them in an old folkloric rhyme:

Veneziani, gran signori;

Padovani, gran dottori;

Vicentini, mangia gatti;

Veronesi, tutti matti.

Freely translated, it gently mocks Venice’s lords, Verona’s cat-eaters, Verona’s lunatics and Padua’s dottori — not medical doctors, necessarily, but graduates of its 800-year-old university.

That’s the regional view. The Padovani themselves call their home la Città delle Tre Senze — the three Withouts: the Caffé Without Doors, the Meadow Without Grass and the Saint Without a Name. But it also has three Withs. It is a city with a glorious chapel, with abundant frescoes, and with many markets.

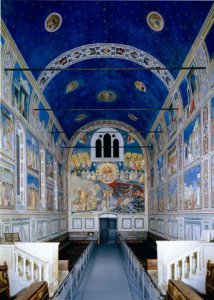

The Scrovegni Chapel, also known as the Arena Chapel is home to an array of frescoes by Giotto

Greatest and most challenging is senza dubbia the Cappella degli Scrovegni, or ScrovegniChapel. Also called the Arena Chapel, it was built about 1305 for Enrico Scrovegni as, tradition holds, an expression of piety and penitence to save his father’s soul from hell. The old man, Reginaldo, had been a banker grown rich from usury — lending money at interest — then one of the gravest of sins. Indeed, Dante had already damned Reginaldo in his Inferno, hurling him into the Inner Ring of Hell’s Seventh Circle, a flaming desert rained upon by fiery flakes from the sky.

Small and plain without but a world of wonders within, the chapel glows beneath a rich blue barrel-vault ceiling, its walls covered end to end with Giotto’s glorious frescoes. Giotto was then at the height of his powers, and these are among the great masterpieces of art. Arranged on the side walls in three tiers of large square panels, they depict episodes from the life of the Virgin, the Nativity, the Passion of Christ, the Resurrection, and the Pentecost. Above the altar God is seen sending a messenger angel to earth; the chancel wall, above the entrance, shows a vast Last Judgment, which includes cameo appearances by our heroes, Enrico Scrovegni and Giotto himself.

|

|

|

|

Giotto’s Last Judgement

|

Jesus turns water into wine

|

The Kiss of Death: Judas betrays Christ

|

An old story: Giotto was said to be plug ugly, and his children likewise. When his friend Dante asked him how he could paint such beautiful figures yet sire such homely offspring, Giotto said “I make the former by day and the latter by night.” Artistically far ahead of their time, the frescoes are alive with sculptural figures and intense emotions. “Giotto threw aside all the glitter, and all the conventionalism, and declared that he saw the sky blue, the tablecloth white, and angels, when he dreamed of them, rosy, and he simply founded the schools of colour in Italy — Venetian, and all,” said John Ruskin. “And what is more, nobody discovered much about colour after him.” Sister Wendy, the endearingly bat-like nun and art expert, was more succinct: “Giotto brought to life the mysteries of faith,” she said, “and art was never the same again.”

The Scrovegni is tricky to find. It’s in the Giardini dell’Arena, a canal-side park of greenery and Roman fragments, and is subsumed into the Museo Civico complex. Hence most signs signal the museum, not the chapel. Solution: enter the museum; you’ll be home free. Another challenge: getting a reservation (required; it may involve a longish line). N.B.: be on time for your visit. Being late may result in a rare instance of Italian severity: having to buy another ticket. Another good reason to give yourself plenty of time is the Museo Civico itself, with its many Roman relics and the fine collection of sacred art given by Padua’s ancient Capodilista family. Solution: buy a PadovaCard online or on arrival (details below) and arrive early, because the chapel is in a separate building. Challenge Three: absorbing it. Solution: come again.

Visits are brief, only 20 minutes, and only for small groups of about two dozen. Before entering, groups enter a kind of airlock for their carbon footprint to be measured and the ventilation system to be adjusted accordingly. That protects the frescoes: like the cave art of Lascaux, they can be quickly and severely damaged by too many people traipsing through too often. Similarly, photos are expressly forbidden. Long term, flash damages artworks. Short term, it takes only one shooter to spoil everyone else’s pleasure. (Plenty of slides and prints are available in the museum’s gift shop.)

More frescoes are the second With, for Giotto and others made Padua the City of Frescoes, but not all have survived. When Fra Giovanni’s Church of the Eremitani fell to an air raid in 1944, the Andrea Mantegnas of the Ovetari Chapel fell with it. A few escaped intact, but others had to be pieced together from the rubble or recreated from old photographs. Domenico Campagnola is well represented in the Sala dei Giganti and (with Stefano dall’ Arzere) in the Basilica and Scuola del Carmine, as are Menabuoi in the Baptistry. So too Altichiero (“among the most excellent of artists’’) and Avanzo (“about whom little is known”), in the Oratorio di San Giorgio. But all of the Giottos in the Palazzo della Ragione were destroyed by fire, as were most of those by Menabuoi.

Il Salone’s roof is like an inverted ship’s hull

Nevertheless, don’t miss this splendid structure, called Il Salone by Padovani and set massively between two open-air produce markets. Fra Giovanni took the Palazzo della Ragione in hand in the early 1300s, when it was the Palace of Justice; he draped it with an elegant lace curtain of arched loggias and topped it with an enormous ship-roofed hall. So called for its resemblane to a capsized hull, a ship roof has no supporting columns, only arched wooden frames like the ribs of old sailing ships. The result is clear, unobstructed space—here wider than a football field and nearly as long. The effect is stunning: the enormous volume is simultaneously enclosure and void, suggesting the Buddhist concept of ‘powerful emptiness.’ In short, it will lift your heart. Not quite compensating for the lost Giottos are their replacements, an astrological-mythological cycle in 300 mysterious panels by Giovanni Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara.

Nearby is one of the Withouts: Caffé Pedrocchi, built in the 1830s, was without doors from the get-go: among the earliest of 24/7 businesses, it never closed. It’s an oddball blend of semi-classical and neo-Egyptian design, and it has an arty history (Byron, Stendahl and Dario Fo have sipped here) plus innumerable university students. Times change: now there are doors and it’s not quite the hive of revolutionary fulminations of the sort that sparked riots in 1848.

Heading south we come to With and Without combined, courtesy of San Antonio. The Padovani are familiar with and possessive of their patron. To them he is always Il Santo, the Saint Without a Name, because he is the saint — as if there were no other. To Padovani the Basilica di San Antonio is simply Il Santo. Indeed, they have no Via San Antonio here, only a Via del Santo instead.

Antonio was inspired by Francis of Assisi; and in time he became a Doctor of the Church known as the Ark of the Covenant and, a bit more menacingly, the Hammer of Heretics, liable, if crossed, to call down heavenly fire upon the faithless head. In short, unlike his mentor, he was a tough customer. Then came the miracle in which, bathed in a holy aura, he was seen holding the infant Jesus in his arms. Antonio himself always modestly played that “miracle” down, but to zero avail. And ever since he’s been (mis)represented as a simpering softie, piously helping travelers, pregnant women and, as manager of the celestial lost-and-found office, people who’ve mislaid their car keys.

The multi-domed basilica of Padua

It is the softie image that infuses Il Santo’s exuberant basilica, which dominates the south end of Padua’s historic center in clamorous contrast to the understated Scrovegni in the north. As much fantasy as church, this seven-domed spire-strewn, cone-capped confection, cousin to Venice’s St. Mark’ s, is a voluptuous and exuberant extravaganza. Never mind Il Santo’s vow of poverty: this is a pilgrimage church, and its extravagance is an expression of pilgrim devotion.

Within, three chapels are of particular interest. The Cappella del Beato Lucahas charming Menabuoi frescoes and the Cappella di San Felice has very fine ones by Altichiero. The basilica’s chief attraction is Il Santo’s own chapel. Designed by Il Riccio, it shows fine marble reliefs by Sansovino and the Lombardo brothers, and is ever thronged by the faithful, who line up patiently to touch or kiss the sarcophagus and offer their prayers.

Donatello is present within and without the basilica. His is the bronze group at the high altar, as well as the towering Paschal Candelabrum (13 feet!), and a dozen bronze reliefs, made with his master, Bellano, in the Choir. Just outside is his equestrian bronze of Gattamelata (Erasmo di Narni), one of the Renaissance’s great condottieri or mercenary captains. Serene and graceful, it is almost diplomatic in aspect. Contrast that with the muscular arrogance Verrocchio expresses in Venice in his bronze of a near-contemporary, the condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni.

We’re on the verge of Stendahl Syndrome now; it’s time for a masterpiece-free rest at another With/Without. A short walk from the basilica is Prato della Valle — the Meadow Without Grass. Flat but marshy, it grew naught but reeds and algae, and when it was reclaimed in 1775, still no grass. Instead it was eventually paved, then pocked with the statuary and water features called Isola Memmia, and finally became recognized as the largest piazza in Italy. It’s an excellent spot for lounging — and the With is its many markets.

Monday through Friday there’s a small fruit and vegetable market (the markets at Il Salone are bigger and better); on Saturday it’s the same but clothing is added. On the third Sunday of every month, antiques and flea-market stuff (my personal favorite) rolls in (my personal favorite) — and sometimes spills into nearby streets as well. Markets are why I eschew hotels for cheap rental apartments. What’s worse than going to a glorious Italian market but not being able to buy for lack of a stove?

There’s much more of course, too much, I sometimes think: the ancient city gates; the Loggia di Gran Guardia; the University, where Galileo taught; the Basilica of Santa Giustina, the grand Botanical Garden. But there’s never enough time in Padua, at least for me. And I’ve been there three times.

Padua Notes:

Padua is easy to navigate. Its historic center is compact but not cramped; it’s also busy: it’s a vital part of the city where people live and work, not a dusty tourist museum. Many principal sites lie on or near a thoroughfare that is, from Prato della Valle to the Scrovegni, not quite a mile long. Just be aware that its names change en route in the Italian style, from Umberto I to Roma to Cavour to Garibaldi. Three buses (Nos. 3, 12 and 18) and a tram serve this route; a mini-bus takes a shorter, more central path. All fares €1.20. Foot-voyagers can download free audio tours at http://www.turismopadova.it/menu-en/medi acenter/soundtouring/i-padova-soundtouri ng-in-citta.

The PadovaCard. This is the visitor’s great saver of time, trouble and money. Admission to the Scrovegni alone is €13 (€6, age 17 and under); the PadovaCard covers that for one adult and a child up to 14 for €16 or €21 for the 48- or 72-hour card. Either includes a free guidebook and free admission to nine other major sites (saving €40 or so in separate admissions); free use of local public buses and trams; reduced admission to 20 other sites in and around Padua;discounts or omaggi (a.k.a. freebies) at selected lodgings, restaurants, bars and shops, plus selected tourist services, the hop-on/hop-off tour bus; and free if somewhat distant parking at Park1, Piazza Y. Rabin, Padua. In short, the PadovaCard is an excellent bargain. It can be bokught at IAT tourist offices, hotels and museums, and can be purchased in advance online:http://www.padovacard.it/eng/index.php. For on-site sale locations see http://www.padovacard.it/eng/e_punti_vendita.php . For my part I prefer avoiding the website, which is a bit clunky (as am I), to buying on arrival. I don’t want to have to make my Scrovegni reservation before I’ve even arrived in the city; also, buying in person means I can tell the clerk exactly what time I want to start the clock ticking on my 24, 48 or 72 hours.

Photos of the Scrovegni Chapel courtesy of and copyrighted by Comune di Padova-Musei Civici Eremitani and Turismo Padova Terme Euganee.

& & &