Bilingual Road Sign

If you still play “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?”, an educational video game first released in 1985, I bet you won’t be able to locate “Hora e Arbëreshëvet” on the world map. I can now, but only because I visited there in mid-July.

Upon arrival and during a short walk up hill to its main square “Hora e Arbëreshëvet” looks like many other small, sleepy towns in Sicily: cobblestone streets, a prominent First World War memorial, shuttered houses abandoned by migrants who long ago left for North and South America or more recently for Northern Italy and Northern Europe, numerous churches, and old men wearing “coppolas” sitting on straw-seated chairs in the shade with no women in sight. Yes, believe or not “Hora e Arbëreshëvet”, in spite of its unpronounceable name is in Sicily, on a plateau at 2,600 feet above sea level surrounded by mountains some 15 miles due south of Palermo. It’s a unique place because of its history, its post-World-War-II politics, its artisanry, and its gastronomy.

So why this weird name? Yes, I really am talking about Sicily, but “Hora e Arbëreshëvet”, with a population today of some 6,200, was founded in the late 15th century by a large group of Albanian refugees whose descendants still live there today and speak Arbërisht or Albanian of the past with Renaissance grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. It derives from the Tosk dialect spoken in southern Albania. In fact, all the official municipal documents and road signs are bilingual here and in the some 20 “Albanian” nearby towns: Santa Cristina Gela, Mezzojuso, Contessa Entellina, Palazzo Adriano, Sant’Angelo Muxaro, Bronte, Biancavilla and San Michele di Ganzaria, to name a few. The Italian law 482/99 protects the language of historical minorities. Wikipedia reports: “Since 2017, with the subscription of the Republic of Albania and Kosovo, an official application for inclusion of the Arbëreshë people has been submitted to the UNESCO List as “a living human and social patrimony of humanity'”.

In 1482-85, after several attacks from the Ottomans, the Christian Albanians were forced to the Adriatic coast where they hired ships from the Republic of Venice and managed to reach the island of Sicily.

Cardinal Giovanni Borgia

On August 4 or 30, 1488 Spanish-born Giovannni Borgia (1446-1503), Archbishop of Monreale, granted them lands in his fiefs known initially as the “Plain of the Archbishop”,” and allowed them to preserve their Orthodox Christian rite. At first the local population referred to the Albanian refugees as “Greeks” because of their Orthodox faith and the Albanian settlement was known as “Piana dei Greci” for over 400 years. In 1941, when Mussolini invaded Greece, he changed the name to “Piana degli Albanesi”, a literal translation of “Hora e Arbëreshëvet” in the hopes of gaining the locals’ support for his fascist regime’s imperialist intentions towards Albania. This seems to me, though I could be wrong, one of “Il Duce“’s arrogant misjudgments because why would people who have spent 400 years preserving their heritage betray their ethnic homeland?

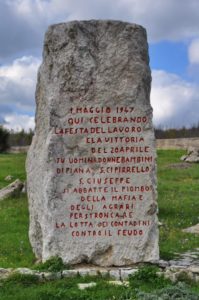

After World War II, on May 1, 1947, twelve days after a Communist victory in regional elections, the Portella della Ginestra massacre took place here in the mountain pass just outside town. It was one of the most violent acts in the history of modern Italian politics. Eleven people, four of them underage, were killed and 27 wounded during May Day celebrations. Although the motives and intentions are sill a matter of controversy, supposedly the Mafia had hired the bandit and separatist leader Salvatore Giuliano to carry out the attack after the communist party leader of Sicily, Girolamo Li Causi, had pledged to redistribute large land holdings. TripAdvisor gives a visit to the on-site memorial, designed in 1979/80 by the distinguished artist Ettore De Concilis, a 4.8/5.0 rating.

Part of the Monument at Portella della Ginestra

Cathedral outside

Cathedral inside

Other recommended sights are several churches: The Cathedral of St. Demetrius Megolomartyr, Church of the Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi built between 1498 and 1590, it preserves some frescoes by the highly respected local painter Pietro Novelli (1603-47), nicknamed by his contemporaries the “Raphael of Sicily”, and the icon of the Madonna and Child (1500); the Church of St. Mary Odigitria on the main square, the only architectural work by Pietro Novelli (1644), preserves a Virgin Odigitria icon said to have been brought here by the earliest Albanian refuges in the 1480s. She is said to have appeared to them and told them to build a church in her honor on this very site; and the Church of St. George, built in 1492, the oldest church in town, preserves some remarkable frescoes.

Also well-worth a visit is the Museum of Nicola Barbato (1856-1923), a native-son medical doctor and socialist, especially for its collection of magnificently embroidered women’s dresses and jewelry. Noteworthy are the bridal gowns’ magnificent brocades, silks embroidered in floral patterns with gold threads, and the solid silver belt buckles given by future mothers-in-laws to brides.

Wedding dress belt

It’s possible to purchase modern versions and other jewelry hand-made by the Lucito family since 1965 and other local handicrafts at “Gli Oro di Piano”, Via P.M. Costantini 3 or on online at www.ordinipiana.palermo.it.

Another local jewel is Piana’s cannoli considered to be the best in the world and the best of all cannoli bakers to be Marco Cuccia. During a visit to his lab and bar, “La Casa del Cannolo”, Via Kastriota 48, I was lucky to have the following chat with Marco, nicknamed “the King of Cannoli”:

Marco Cuccia

Your first memories of food?

Potato omelets.

Your first memories of cannoli?

My mother frying their shells and the aroma spreading throughout our home.

Who was the first member of your family to be a pastry/cannoli chef?

My mother and my father.

Piana degli Albanesi is a small town with only inhabitants but eight cannoli producers; how do you manage having so many competitors?

Counting on the superior quality of our product.

Your surname sounds Italian; so that must mean that your ancestors weren’t Albanian but you were born in Piana degli Albanesi?

Yes, I was born in Piana and my ancestors were Albanian.

Do you speak Arbëresh?

Yes, all the time, both at work and at home.

How come there are so many cannoli chefs here in Piana? When were they first produced?

There are a few legends about the origins of cannoli in harems or nunneries, but the first historical document mentioning them: tubus farinarius dulcissimo edulio ex lacte facto (a flour-based cylinder-shaped pastry made with milk) is by Cicero when he was quaestor in Sicily. More recently, I don’t know the exact date, but the sisters of Maria Odigitria ran the first “bakery” to produce them.

The cannoli from Piana degli Albanesi are considered the best in the world, how are they different from those in Palermo, Trapani or Erice, the town also very famous for pastries?

Because we make our shells by hand and the ricotta in our filling is Km. 0 made with sheep’s milk.

Does the cannolo have an historical connection specifically to Albania or with the Middle East in general?

Not specifically with Albania, but of course with the Middle East.

How are your cannoli different from those of the other seven pastry chefs’ here?

You have to take my word for it that mine are the best. I can guarantee you, but you can of course try those of my seven competitors. It’s a free country.

When we arrived here in Piana degli Albanesi, you invited us into your laboratory and explained to how to make a cannolo. However, there was too much noise and I missed some steps, so can you repeat your recipe for my readers?

Flour, vinegar, sugar, animal fat, are the shell’s ingredients. You mix them together, roll out the dough, cut out and roll the shells, and fry them.

How many cannoli do you make a day?

We make cannoli on Tuesdays and Thursdays, around 1,000 each of those days.

What’s the best drink to enjoy with a cannolo?

A sweet wine in particular Marsala Ambra.

Speaking of wines, be sure to stay at the nearby elegant winery resort, “Baglio di Pianetto” with tastings, spa, magnificent grounds, and a world-class restaurant, Pianeta Bandolo. Founded in 1997 by Count Paolo Marzotto and his French wife Florence, since 2016 its knowledgeable yet modest managing director is gracious Renato De Bartoli, whose father Marco is the renowned wine producer from Marsala.

Renato De Bartolo

Besides “Baglio di Pianetto”’s, the Marzotto own “Tenuta Baroni” near Noto. In their two vineyards, some 220 acres all together, the Marzotto cultivate the most important varieties of grapes autochthonous to Sicily: Nero D’Avola, il Grillo, l’Insolia, il Cataratto, and some international varieties like Syrah, Merlot, Petit Verdot, and il Viognier. They produce some 600,000 bottles per year with 19 different labels. They export 40%, their top markets being Germany and Russia. Their autochthonous wines are their most successful; their top seller universally is Shymer, in the USA they’re Nero D’Avola and Monovarietale BIo and in Italy Ficiligno.

“The cantina at ‘Baglio di Pianetto’, Maurizio Turrisi of the PR Office told me, “built between 2001 and 2003, was purposely developed vertically on four floors, two above and two below ground (the lowest being some 105 feet underground) which take advantage of the constant temperature and of the gravity, thereby drastically reducing the use of pumps which causes stress to the wines. The wines, made of grapes grown exclusively from our vineyards, are aged in barriques and barrels made of French, American and Slavonian (the region of Croatia) oak.”

Florence Marzotto’s portrait on barrel

Paolo Marzotto’s portrait on barrel