The absence of tourists unsettled by the recent terrorist attacks makes this an excellent time to visit to the City of Light.

‘They must be right,’ I said. ‘The official word is that tourism’s down twenty percent, and it certainly looks it.’ I was talking to Valerie Bloch, owner of one of the shiny new little shops that these days are sprouted by entrepreneurial young Parisians like post-rain mushrooms. Her shop, Marchande de Saveurs, sells an imaginative selection of specialty food products from small French producers — only these days, she’s not selling much. ‘Twenty percent?’ she said. An eye-roll showed she wasn’t having any of it. ‘More like fifty. Where are the Americans? They’re clearly not here, they’re not coming. And the Japanese? They’re not coming either, so the city seems empty.’

But only seems. Although I can sympathize with the retail point of view, for my two mid-October weeks Paris lay nicely between empty and gratifyingly uncrowded. The exchange rate is at it most favorable in months, with the dollar rising and the euro sinking, but still the bateaux mouches that normally pack the Seine almost stem to stern were widely separated and lightly populated, their passengers nearly all finding seats on their open upper decks and hardly any of them packed between the glass-walled lower decks. As for street life, at what the French call ‘the hour between dog and wolf’ — i.e., dusk — the cafés were lively but loosely packed, with tables readily available inside and out, the bistros likewise and, I suspect, the star-level ‘restos,’ too. There were also the autumnal sun, with its warm light, and crisp autumnal breezes. And the city was alive with art. Especially with art.

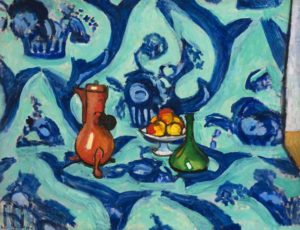

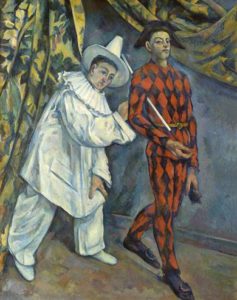

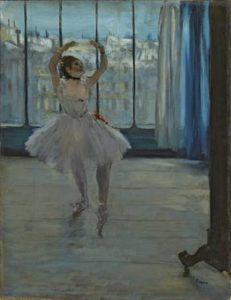

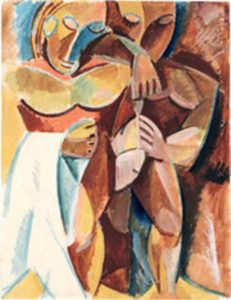

The great event of the season is ‘Icons of Modern Art’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, in the Bois de Boulogne. Outside, Frank Gehry’s vast, ship-like structure has had its mighty, full-breasted ‘sails’ striped with panels of blue, green, orange and red by the French conceptual artist Daniel Buren, who has transformed it into ‘The Observatory of Light.’ Inside, the museum is again transformed — conquered, even — by the ‘Icons’: 127 paintings by Matisse, Gauguin, Picasso, Van Gogh, Cézanne, Degas and other giants of Impressionist, post-Impressionist and Modern art.

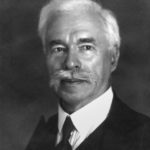

Sergei Shchukin

All are from the collection of Sergei Shchukin (Chtchoukine, in the French rendering), and this is the only time they have left Russia since they were nationalized by Lenin soon after World War I.

Inheritor of his father’s fabrics business, Shchukin was magnate enough to live lordly in his Trubetzkoy Palace, travel often to Paris, and spend freely. His taste in art had been apparently almost boring until his Paris-based brother, Ivan, and Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel changed his life — and his collecting. From 1898 and 1914 Shchukin went on a buying spree — a frenzy, even — and amassed 275 paintings, some of which, such as Matisse’s ‘La Danse’ and ‘La Musique,’ he commissioned.

It is difficult to convey the extent of the collection, long regarded as one of the world’s most important collections of early 20th Century modern art, without resorting to the crudity of numbers: a whole roomful of Picassos — 50 of them — here, a roomful of Matisses there. Thirteen Monets, eight Cézannes, four Van Goghs, 16 Tahiti-period Gauguins. As well as works by George Braque, Henri Rousseau, Gustave Courbet, Maurice Denis, André Derain, Albert Marquet, and others. The collection’s value has been estimated at $10 billion.

Shchukin’s motivations are the subject of some dispute. Some consider that he himself was an artist, in that his collection was by way of painting with paintings; at any rate, his visionary mission is undeniable. He made the Trubetzkoy a museum, the moderns clashing violently with the Neo-Classical fripperies of its interiors, and it powerfully influenced the young Muscovite artists who flocked to it. Evidence lies in the 30 paintings by Russian ‘progeny artists,’ such as Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Kliun and Vladimir Tatlin, that accompany the “Icons” exhibition. Others suggest that by collecting he assuaged his grief for the deaths of his wife, two sons, and brother Ivan, all within a span of four years. The fact that his buying spree ended in 1914, the same year he remarried, makes that plausible, but he remains an enigma.

He has even been called a mere show-off who collected merely to impress his wealthy peers. If so, it didn’t work out: they scorned his art, said he’d been duped by wily French dealers. They were not alone. Came the Revolution and Shchukin wisely skedaddled to Paris, even though it meant leaving his collection behind. It was confiscated under Lenin but soon fell into disfavor as ‘bourgeois’ art. Tractor Art, a.k.a. Socialist Realism, was officialized in the Soviet Union, and under Stalin the collection was dispersed, dismissed as ‘not socialist’ — that is, merely decorative and of no practical use, hence decadent besides. (One soviet minister actually suggested destroying the lot of them).  After spending World War II in Siberia the collection was eventually divided between the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. In all, there’s something miraculous about its survival, as there is about its arrival in Paris: Shchukin has living heirs, and the Russians insisted on official guarantees that the works would not be subject to restitution claims. ‘Icons’ is also an example of poetic justice: bourgeois art collected by one of Russia’s last capitalists is at last brought to a wider public by France’s best-known capitalist, Bernard Arnault. He is president of the Vuitton Foundation, grand manitou of the luxury-goods conglomerate LVMH, and, in short, in brief and in a nutshell, the richest man in France.

After spending World War II in Siberia the collection was eventually divided between the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. In all, there’s something miraculous about its survival, as there is about its arrival in Paris: Shchukin has living heirs, and the Russians insisted on official guarantees that the works would not be subject to restitution claims. ‘Icons’ is also an example of poetic justice: bourgeois art collected by one of Russia’s last capitalists is at last brought to a wider public by France’s best-known capitalist, Bernard Arnault. He is president of the Vuitton Foundation, grand manitou of the luxury-goods conglomerate LVMH, and, in short, in brief and in a nutshell, the richest man in France.

‘Icons’ is the absolute must-see of Paris this season — and only this season. It closes Feb. 20, so there’s reason to hurry. It would be wise to start early in the day and stay late, perhaps taking a break at Le Frank, the museum’s own ‘resto’ (book on arrival if not before), as the weight of so much artistic genius threatens to overwhelm the viewer with Stendhal Syndrome. Even better: see it twice, if possible. Of course there are other fine museums. In the Tuileries, L’Orangerie displays Monet’s “Water Lilies” cycle in a serene, simple, uncluttered setting under natural light, and below stairs, as it were, there’s the excellent ‘Age of Anxiety’: American art of the 1930s. The Musée d’Orsay, worth a detour solely for its soaring conversion from train station to art museum (by the Italian architect Gae Aulenti), has a splendid hoard of Impressionists and post-Impressionists on its top level, and there’s even comic relief in the ground-floor exhibition on the age of Napoleon III — the third quarter of the 19th Century. (That was France’s Yuppie era; the baubles displayed here proclaim that never was so much filthy lucre and high craftsmanship wasted on such pretentious foolery). Centre Pompidou makes its claim, as do the Musée Picasso and the Louvre, among others. But here’s the thing: they’ll be here when ‘Icons’ has melted away, and that will be long before the thaw.

And above all Paris herself makes her claim. Yes, she has felt the wound, but terrorism is not hanging above all like a grey cloud; Parisians do not go about with their heads shrunk turtle-like between their shoulders; the streets are not ruled by glumly staring squads of submachinegun-toting soldiers clad in riot gear and camouflage. Paris is not an armed camp. She lives. Go.

IF YOU GO

Tickets to “Icons of Modern Art” are 16€ for individuals; there are family and student rates: “Icons of Modern Art.” They can be ordered online at https://billetterie.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/billet-fondation-chtchoukine-22-octobre-2016-au-20-fevrier-2017-expo-css5-fondationlouisvuitton-lgen-pg51-ei430761.html.

Fondation Louis Vuitton is easily reached by Metro Line 1. Exit at the Charles de Gaulle/L’Etoile stop and proceed by dedicated navette (shuttle bus), 1€, 5 or 10 minutes, depending on traffic. Alternatively, continue to the Les Sablons stop for a pleasant walk, about 20 minutes, down Boulevard des Sablons, through a posh residential area and then the Bois de Boulogne.

More information:

L’Orangerie: http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en

Musée d’Orsay: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/home.html

Musée Picasso: http://www.museepicassoparis.fr/en/

Centre Pompidou: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en

The Louvre: http://www.louvre.fr/en (Best access is NOT through the Pyramid. Take Metro line 1, exit at Palais Royale-Louvre and enter through the underground Carrousel du Louvre. Lines there are typically much shorter and sometimes non-existent).

PASSES:

Passes for tourist sites and museums exist in plenitude; a few taps in Google will lead you to these and many others:

Read the offering with care; some aren’t worth their cost unless you pack a large number of sites or Metro trips into a very few days; others let you skip the lines at various sites.

GUIDE BOOKS:

Out of print but available from Amazon’s used department, ’Paris,’ by Dana Facaros and Michael Pauls, is far and away the best Paris guide book I’ve ever come across: witty, informative, sly, amusing, literate. It was last updated in 2004, but I used that edition exclusively last month and it never steered me wrong.

David Downie, who has lived in Paris for many decades, can’t stop himself from ceaselessly exploring it and writing about it — and his obsession is to our benefit. His ‘A Passion for Paris: Romanticism and Romance in the City of Light’ is the result of his relentless explorations, and its focus is on the 19th Century. The period is remarkable for two things. One, Baron Haussmann, at the behest of the Emperor Napoleon III, ripped the slum-ridden heart out of Paris and gave us the physical city we know today. (Haussmann’s reconstruction is what makes Paris the City of Light. His broad boulevards, faced with new buildings, all of nearly the same height, all with similar façades, and all of the same reflective creamy color, make daylight last so much longer here than it does in skyscraper cities). Two, a large and astonishing constellation of artists, writers, painters and others arose in Paris and made it a capital of artistic ferment. Downie, who is an inveterate flaneur or ‘urban saunterer and idler,’ has trod all over Paris, visiting and sometimes discovering the haunts of Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, Honoré de Balzac, George Sand, Eugène Delacroix, Alexandre Dumas, Émile Zola, Félix Nadar, Chopin and many more. He knows who they loved or married or betrayed, who slept with whom and who feuded with whom (and with what result: gunfire was not unknown). He knows where the bodies are buried and even what park benches they sat on. This astonishing book, which includes many photos by Alison Harris, Downie’s wife, is virtually a trip to Paris between hard covers. (‘Paris, Paris: Journey into the City of Light,’ Downie’s memoir of how he arrived in Paris as a besotted youth who dreamt of nothing else and somehow managed to neither starve nor freeze to death, is also well worth reading).

For a break from the intensity of urban life you can’t do better than ‘An Hour from Paris.’ Annabel Simms, who has lived in the city for more than a quarter-century, well knows how to get away from it — quickly, easily and cheaply — and find relief that almost no tourists and even a few locals never find. What she offers is a series of nearly two dozen easy day trips, all accessible by public transport, all provided with walking tours and contact information to help readers get the most out of such delights as the Renoir-esque atmosphere of a guingette or country dance hall; medieval Provins; Moret-sur-Loing, whose river and canal were much favored by the painters Alfred Sisley, Monet and Pissaro; Poissy, on the Seine, with Le Corbusier’s famous Villa Savoye, a handsome old restaurant built on a bend of the river, and the charming Toy Museum; and more. Finally, for lagniappe, Simms throws in a short chapter on such standard tourist lures as Monet’s water garden at Giverny (lovely, but increasingly crowded as the blooms advance, and at any season it’s wise go early in the morning), the now-restored palace and grounds of Fontainebleau (go) and pompous, pretentious Versailles (don’t).

Also worthy of interest: ‘Hemingway’s Paris: A User’s Guide’; ‘Permanent Parisians: An Illustrated Guide to the Cemetaries of Paris” (but just between us, I’d give Montparnasse a pass); and Patricia Wells’s ‘The Food Lover’s Guide to Paris: The Best Restaurants, Bistros, Cafés, Markets, Bakeries, and More.’

Bon voyage!